Topographies of Power

Note: For an interactive version of the maps, please go to the desktop version.

General Maps

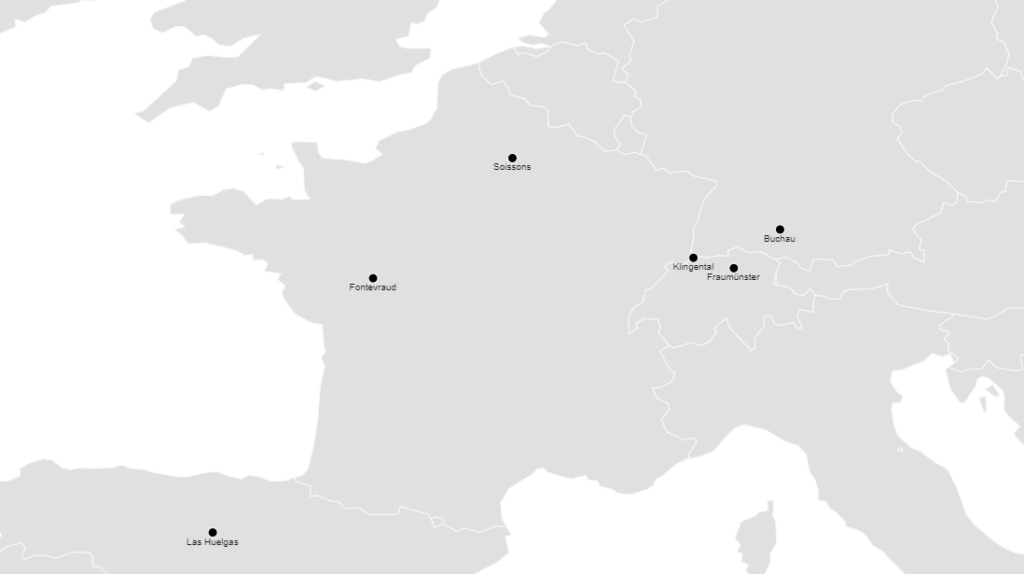

The Samples : The Position of the Monasteries in Europe - Notre-Dame de Soissons, Buchau, Fraumünster, Fontevraud, Las Huelgas and Klingental

The main examples on the website are the monasteries of Fontevraud, Notre-Dame de Soissons, Klingental, Buchau, Fraumünster and Las Huelgas. The map shows their localization. Although, or rather because, the monasteries were spread over a large geographical area, they are very good case studies that allow us to gain insights into life in (aristocratic) women’s monasteries in continental Europe.

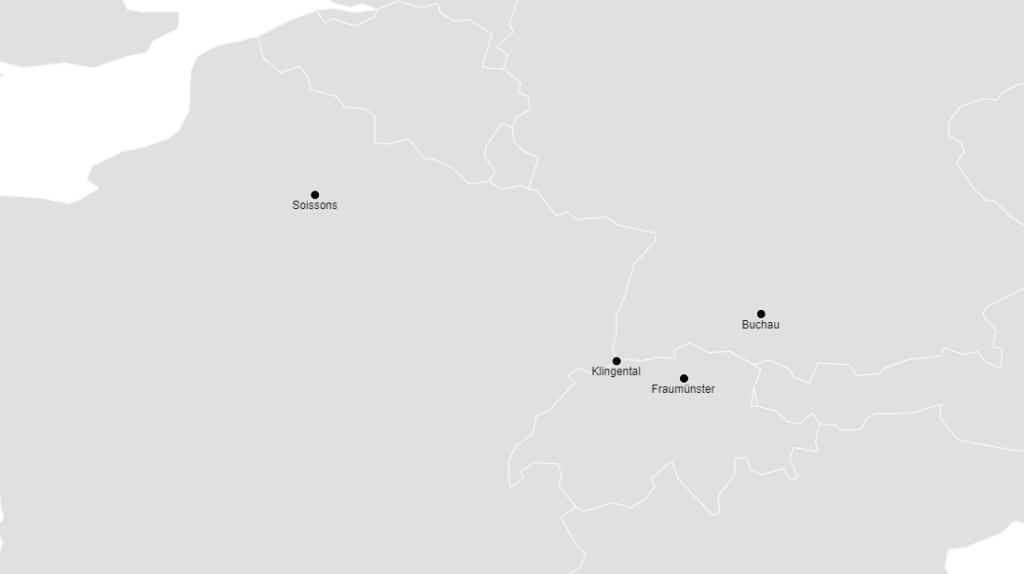

The Samples : The Location of the Monasteries in Europe - Notre-Dame de Soissons, Buchau, Fraumünster and Klingental

The monasteries of Notre-Dame de Soissons, Klingental, Buchau and Fraumünster are the subject of a multi-year research project funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation. The research results will be published in a monograph in 2023. However, many of the research results will find their way into the website rulingwomen.ch before the monograph’s publication.

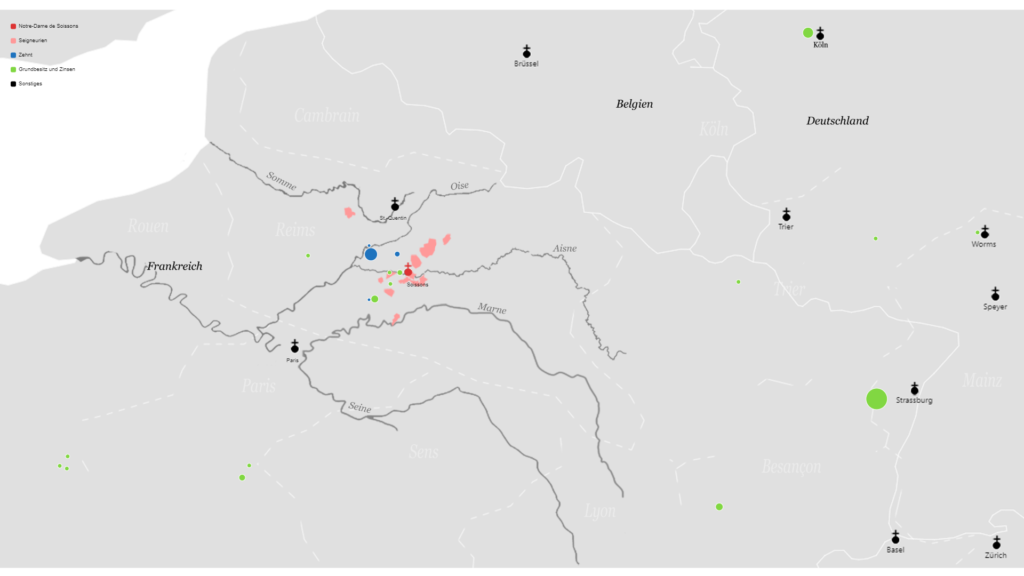

Notre-Dame de Soissons

[Benedictine nuns, abbey, c. 666-1792]

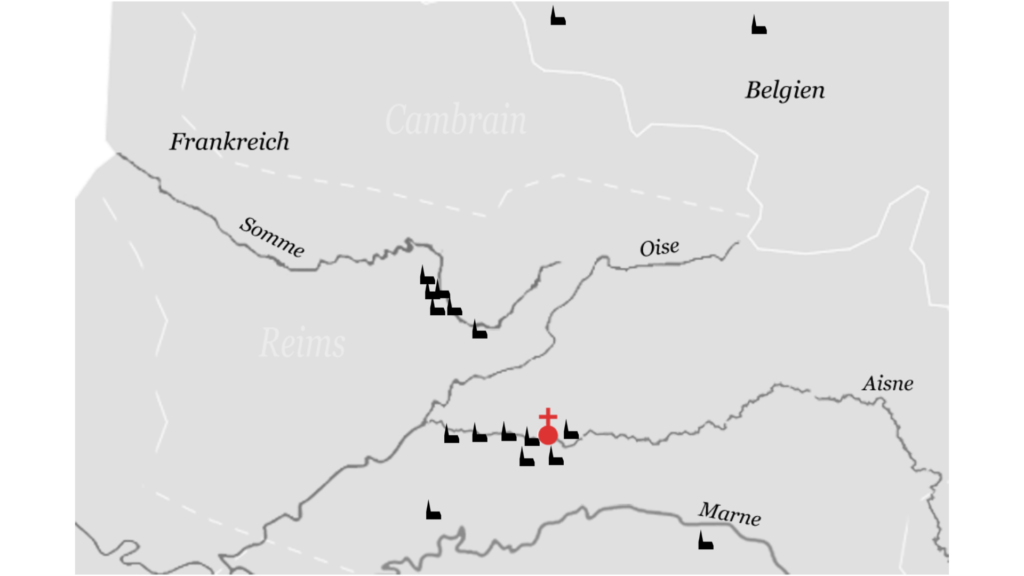

Churches with Patronage Rights

Medieval abbesses not only presided over their community and sometimes administered extensive estates, but they also appointed priests. The right to appoint priests of a subordinate parish is called patronage (Latin: jus patronatus). The abbess of Notre-Dame de Soissons appointed the priests in at least 18 parishes. These parishes were mostly within the abbey’s seigneuries. As spiritual landlady, the abbess was not only responsible for the protection of her people, but also had to ensure their pastoral care.

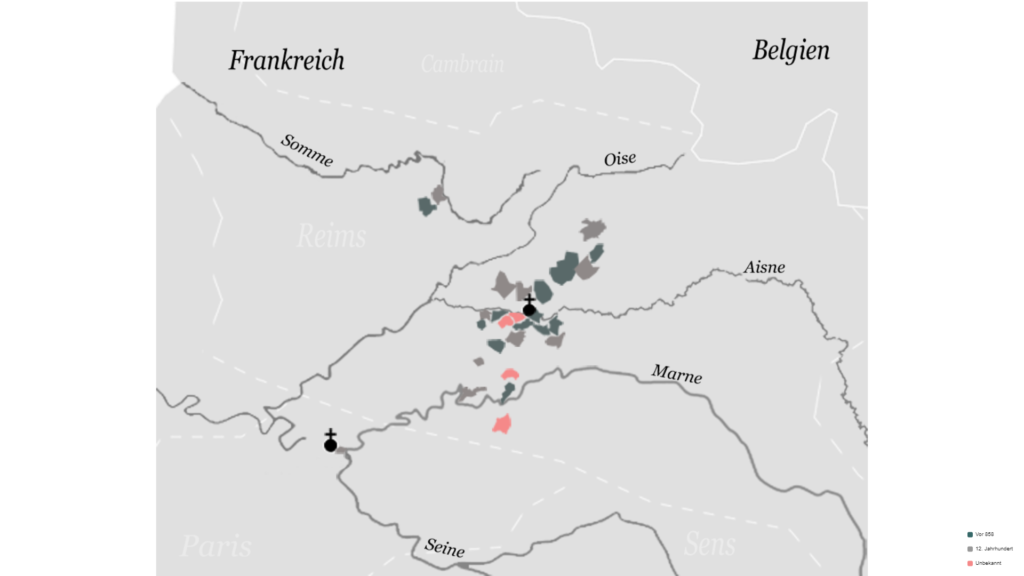

Landlordships by Centuries

This map reveals the territorial policy of the abbesses of Notre-Dame de Soissons. Over the centuries, the abbesses of Notre-Dame gradually consolidated the abbey’s possessions geographically. The abbey also succeeded in more than doubling the Notre-Dame’s seigneuries in the late Middle Ages, namely from 11 in the 9th century to 25 in the 13th century. In all its manors, the abbey had the right to hold court over its subjects. The abbess had this prerogative exercised by bailiffs whom she appointed and who ensured law and order in the respective manor.

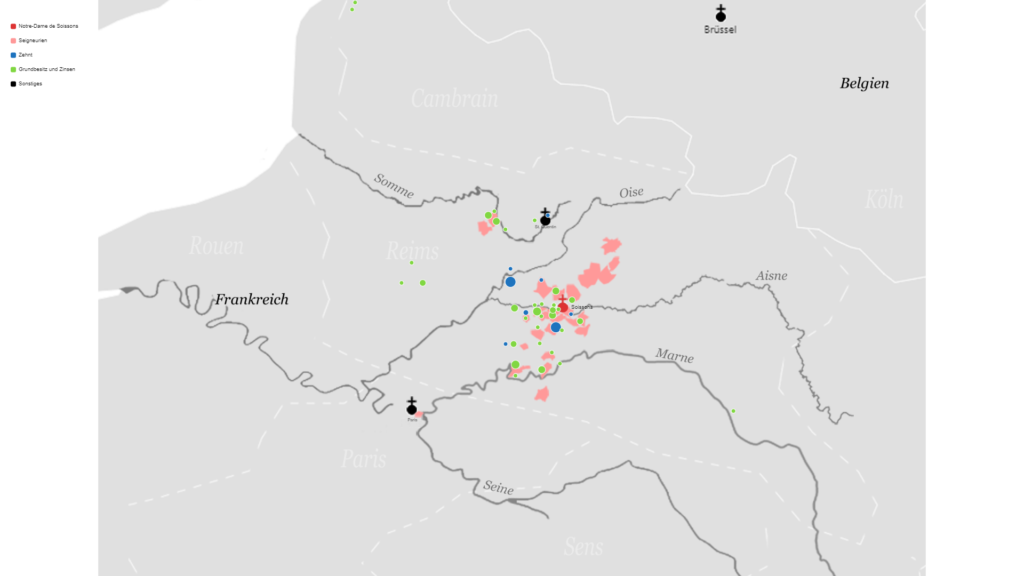

Landlordship and Property

Landlordship and Property in the Early Middle Ages

According to a confirmation of King Charles the Bald from 858, Notre-Dame owned eleven seigneuries in the 9th century, 78 vineyards in and around Soissons, twelve houses in the town itself, as well as a total of 508 farms including serf peasants. In addition, the abbey held various lands as fiefs. The majority of these monastic possessions were located in the Soissons region and were presumably already part of the abbey’s original endowment. But Notre-Dame also had possessions further afield, namely in Alsace, where Notre-Dame held seven fiefs, among others. And near Cologne, the abbey owned 59 farms as well as a village near Worms.

As one can easily see from the list and its representation on the map, Notre-Dame was a rich monastery from the beginning – in the sense of an extensive territorial endowment. However, even Soisson’s early abbesses faced the challenge of solving the problem of distances. For example, there is a good 350 km between Cologne and Soissons alone. According to Google maps, this corresponds to a 74-hour hike on modern roads, that is. With the poor roads in the early Middle Ages, the journey would have been much longer. In other words, these possessions were at a very long distance from the abbey, complicating their effective administration.

Landlordship and Property in the Late Middle Ages

Comparing the maps of Notre Dame’s possessions from the 9th and 14th centuries, it is easy to see that Notre Dame geographically condensed its possessions in the late Middle Ages. More distant possessions were disposed of and closer ones were bought. The extensive sources on Notre-Dame allow us to reconstruct the territorial policy of the abbesses of the 13th century. This is particularly true of the abbacy of Odeline de Trachy, who presided over Notre-Dame between 1256 and 1273. Under Odeline’s administration, individual plots of land, fields, woods and farms were bought up within Notre-Dame’s seigneuries, each adjoining land already belonging to the monastery. The objective of this policy was to establish a monopoly of possession within the abey’s seigneuries – and thus to centre all power in the hands of the abbey.

Buchau [Canonesses, c. 770-1803]

Churches with Patronage Rights

Many of Buchau’s patronages were not confirmed in writing until the 14th century, but we may assume that the abbey already had the jus patronatus in earlier centuries.

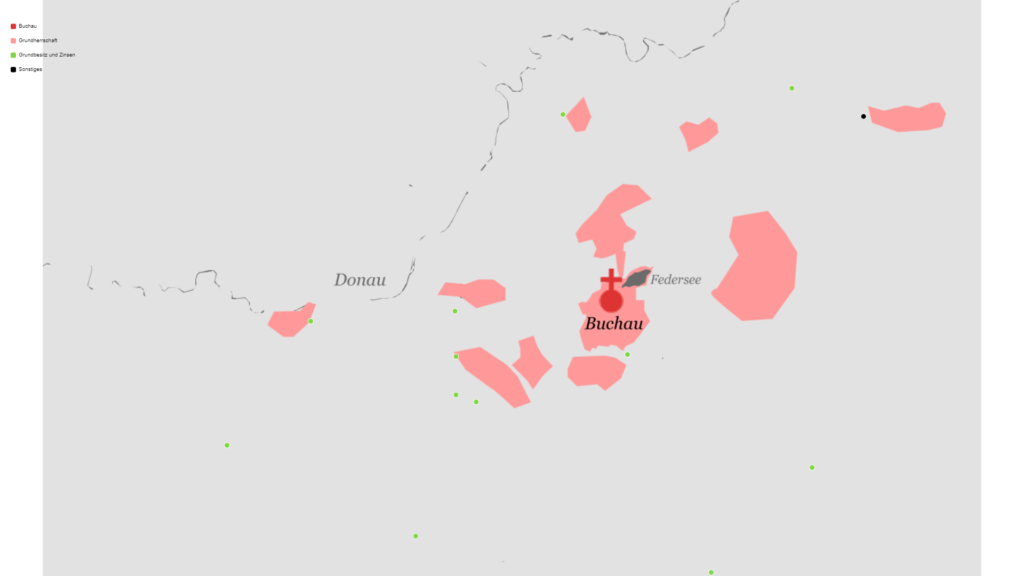

Landlordship and Property in the Early Middle Ages

It is particularly difficult to determine Buchau’s ownership in the early Middle Ages, as most sources from this period are lost or lacking in concrete information. Thus, in 999, Otto III. (996-1002) confirmed all of Buchau’s documented possessions without, however, listing them indiviudally. Only from the late 13th century and then from the 14th century are there clearer findings on Buchau’s possessions.

Landlordship and Property in the Late Middle Ages

The first surviving Urbar, i.e. lists of property rights, from Buchau date from the 15th century. While Buchau sold a lot of scattered property to other monasteries in its vicinity in the 13th and 14th centuries, there was a large increase in property and tithe rights in the 15th and 16th centuries. Buchau’s landholdings and rights extended to over 60 places in the late 15th century. These were generally distributed within a radius of about 30 kilometres around Buchau and were focused on the villages of Saulgau and Buchau itself. Exceptions are mainly the villages of Strassberg, where Buchau had sovereign rights – Ulm, where Buchau had burgher rights – or isolated landholdings in the south near Lake Constance.

The map shows the situation at the end of the 15th century.

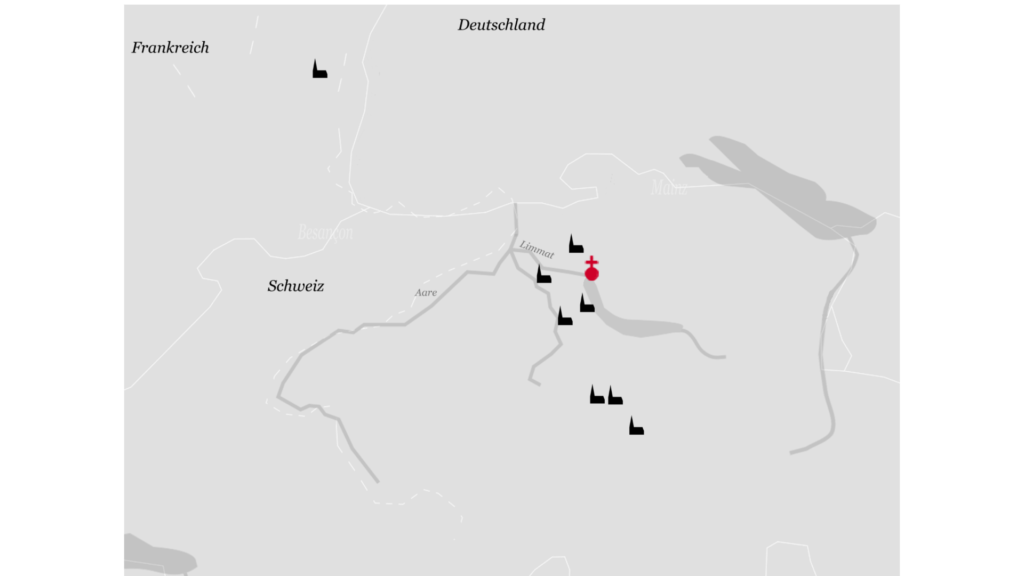

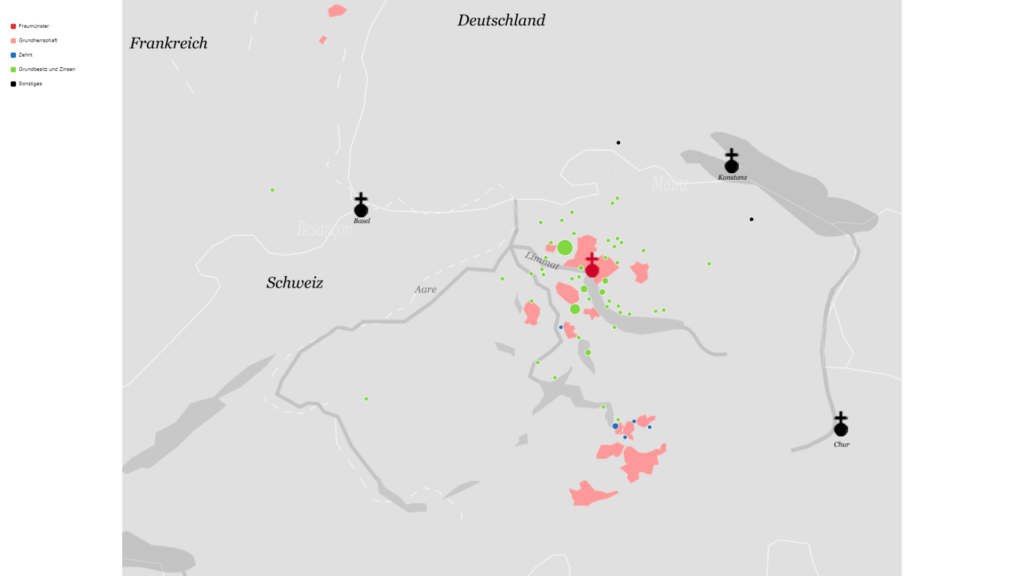

Fraumünster [Benedictine nuns, (princely) abbey, 853-1524].

Churches with Patronage Rights

Landlordship and Property

Landlordship and Property in the Early and High Middle Ages

The early endowment of the Fraumünster included, in addition to Zurich itself, extensive possessions in the present-day Swiss cantons of Aargau, Lucerne, Zug and Uri. As the map shows, the early possessions of Fraumünster resulted in a relatively connected territory, which also included 55 villages with about 120 serfs. Zurich’s abbess was thus not only mistress of the nascent city, but also an important ruler over the surrounding countryside. The majority of the early possessions came from Louis the German (843-867), the founder of the Fraumünster.

Landlordship and Property in the Late Middle Ages

While Fraumünster Abbey had disposed of a large and relatively connected territory in the High Middle Ages, it had shrunk considerably by the 15th century. Fraumünster repeatedly faced economic challenges in the late Middle Ages. The dues the abbey received from its manors and farms were usually paid in kind. As a result, the abbey was chronically short of money. The nuns’ lavish lifestyle, who were mainly recruited from aristocratic families from Thurgau, Aargau and the Baden region, also cost a lot of money. In the late Middle Ages, each nun maintained her own household, rather than living in community. In order to pay the costs, the abbesses had to repeatedly sell possessions in the course of the late Middle Ages. Especially during the abbacies of Fides von Klingen (1340-1358) and Anastasia von Hohenklingen (1413-1429), significant parts of the abbey’s patrimony was alienated. In particular, revenues from Lake Zurich along with tithe rights and property in the Uri Valley.

The map shows the situation around 1430.

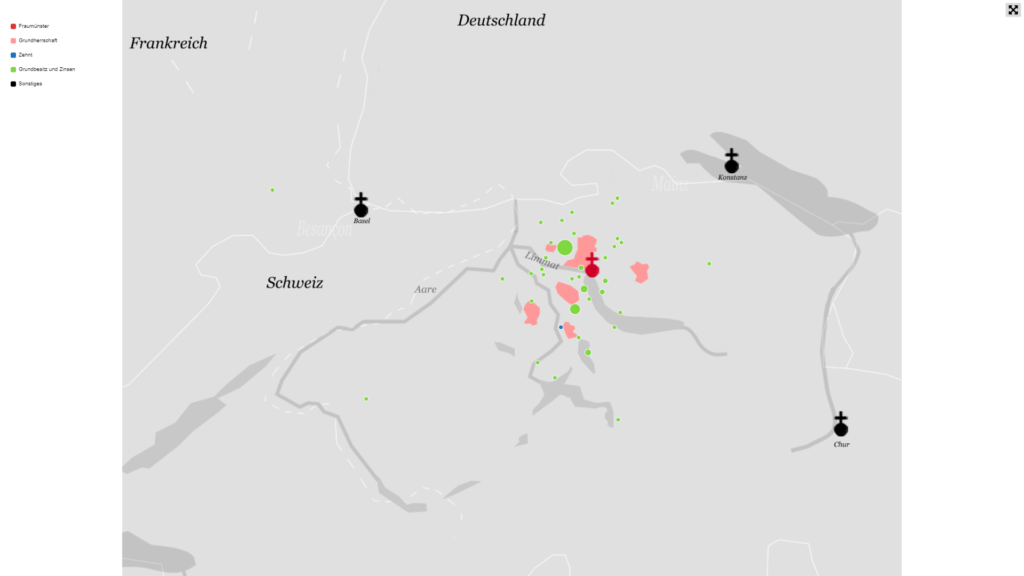

Fontevraud [Fontevrists, Abbey and Order, 1100-1792].

Dominions and Priories

Unlike the other examples, Fontevraud Abbey was at the head of an entire monastic order: the Fontevrist Order. The map shows the distribution of Fontevrist priories, which spread like a crescent from Picardy in the north to the Pyrenees in the south. Only those priories and possessions that have been reliably identified are shown on the map. However, the actual territorial possessions of the abbey and the order were many times higher. The extensive source material on Fontevraud’s possessions, which is housed in the Archives départementales de Maine-et-Loire, has yet to be studied.

The map shows the situation at the end of the Middle Ages (around 1500).

Map from: Müller, A., From the Cloister to the State. Fontevraud and the Making of Bourbon France (1642-1100), London 2021.

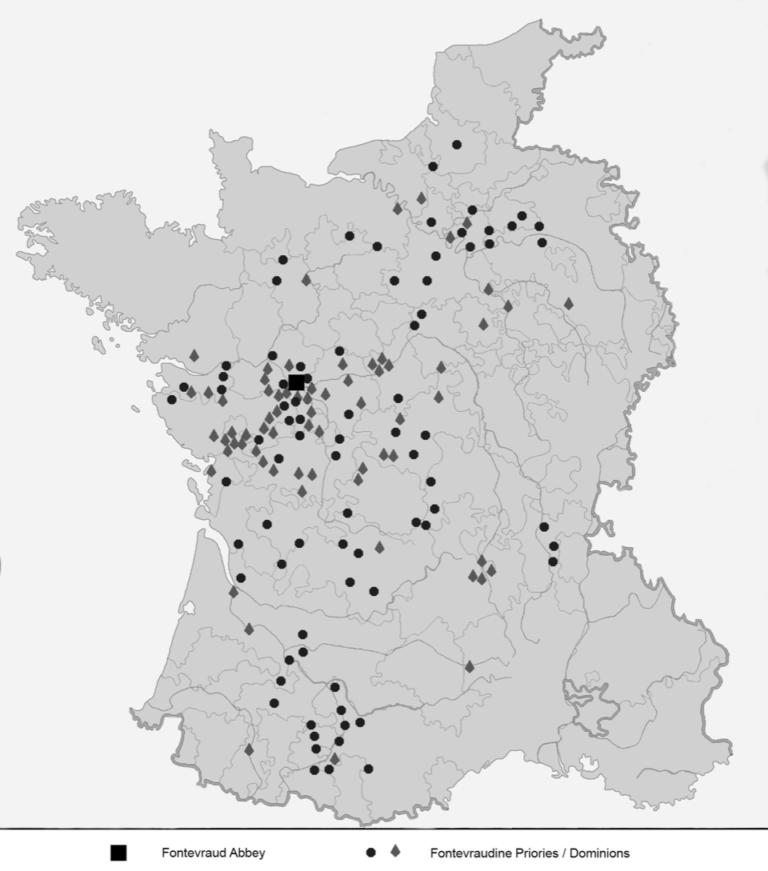

Las Huelgas [Cistercian nuns, abbey, 1187- present].

Sovereign rights and Property

Sovereign Rights and Possessions in the Province of Burgos

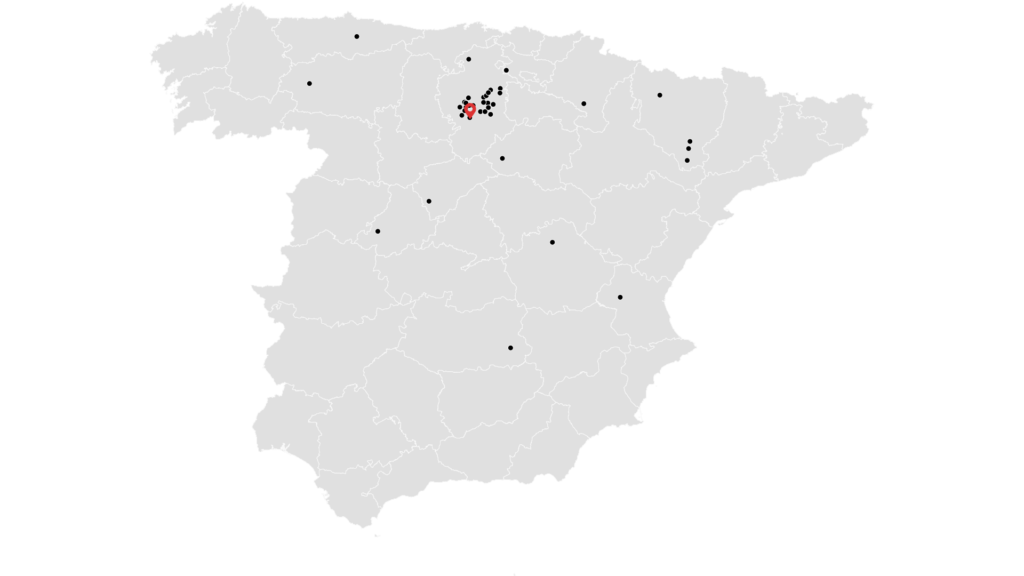

Klingental [Dominican nuns, later Augustinian choir women, convent, 1236-1557].

Klingental's property in Basel on the Merian Plan (1642)

Here on the Merian map of 1642, some of the houses and other property of Klingental are marked in colour. Unfortunately, the location of many of the houses Klingental owned can no longer be precisely determined. In total, on the left bank of the Rhine Klingental owned three farms in Basel with serfs, over thirty houses, nine vineyards and four fields, along with several unspecified estates. In Klein-Basel, on the right bank of the Rhine, Klingental owned gardens, several houses, about thirteen fields/meadows and six vineyards, five farms, including a brickyard, three mills, a sawmill and some serfs. In the 15th century, Klingental even acquired several saffron fields from the city of Basel. Because of this property, Klingental received many different forms of revenues, making it a very rich monastery.

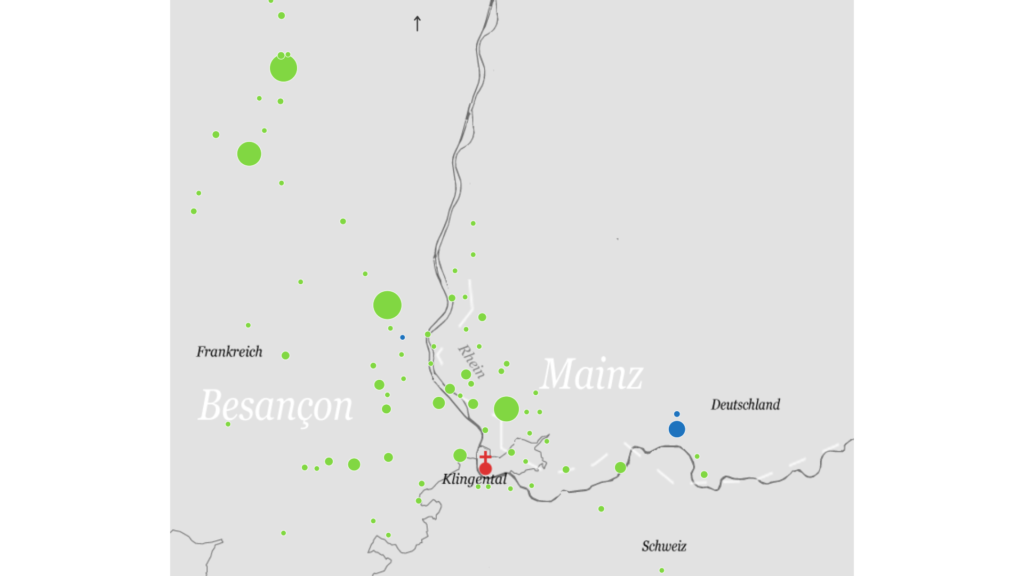

The map shows Klingental Monastery in red, the houses owned by Klingental in green, interest received by Klingental in yellow and agricultural property in blue. The map shows Klingental’s possessions and select revenues in the period from the 13th to the 15th century.

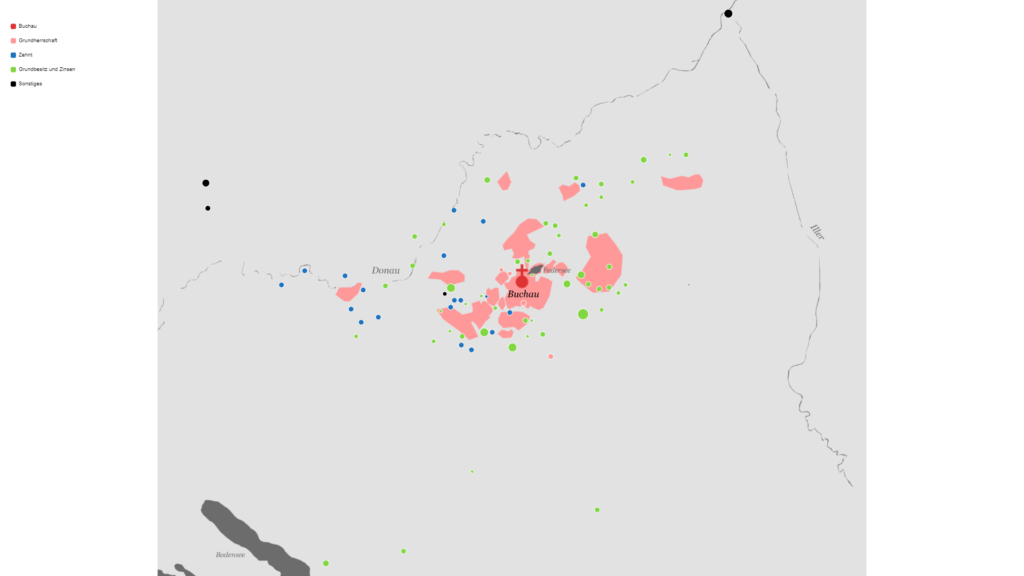

Possession and Interest

Klingental’s itinerary history left traces in Klingental’s possessions. Its patrimony was distributed in the border triangle around France, Germany and Switzerland. Around Rouffach, Habsheim and Sulz in France, as well as Öttlingen and Wehr, and the Wehra valley in Germany, Klingental owned many fields, forests and houses. In the Wehra valley, Klingental further owned tithe rights. Since the middle of the 13th century, the prioress exercised the jus patronatus in Wehr. In Switzerland, Klingental’s possessions were mainly in Klein-Basel and Basel, which is shown on the map above.

The map shows Klingental’s possessions in the 14th century.

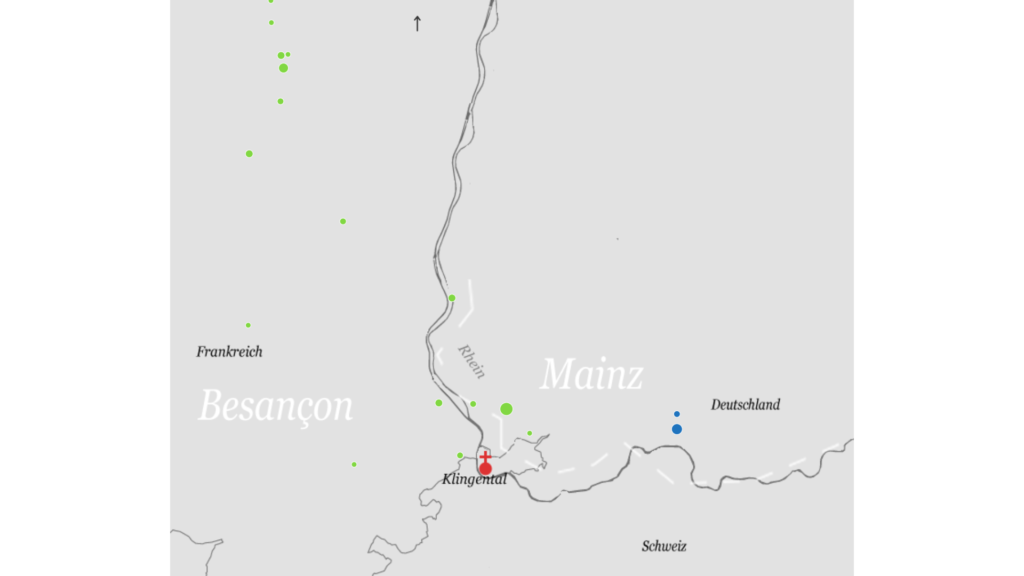

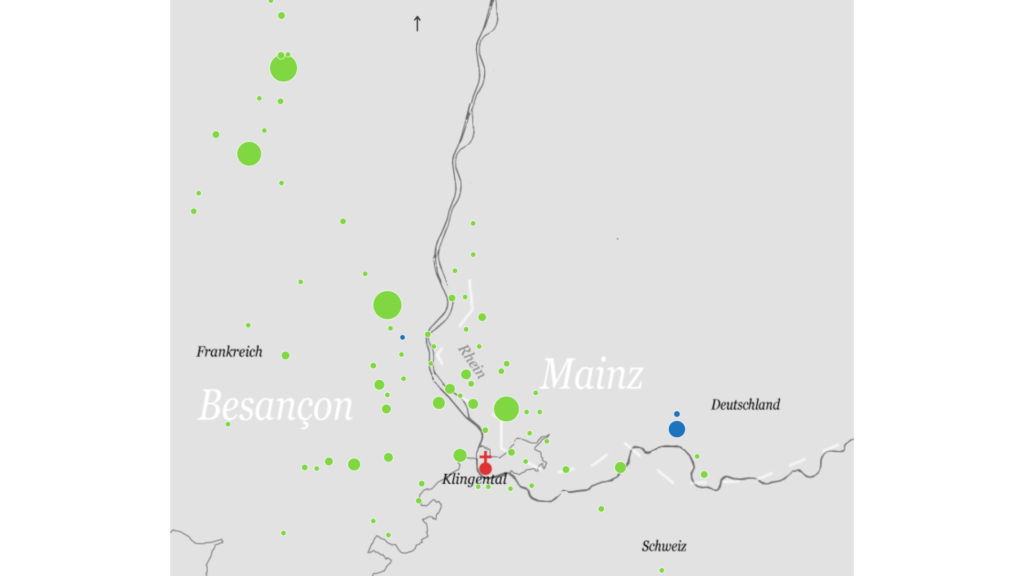

Comparison of Possession 13th / 14th Century

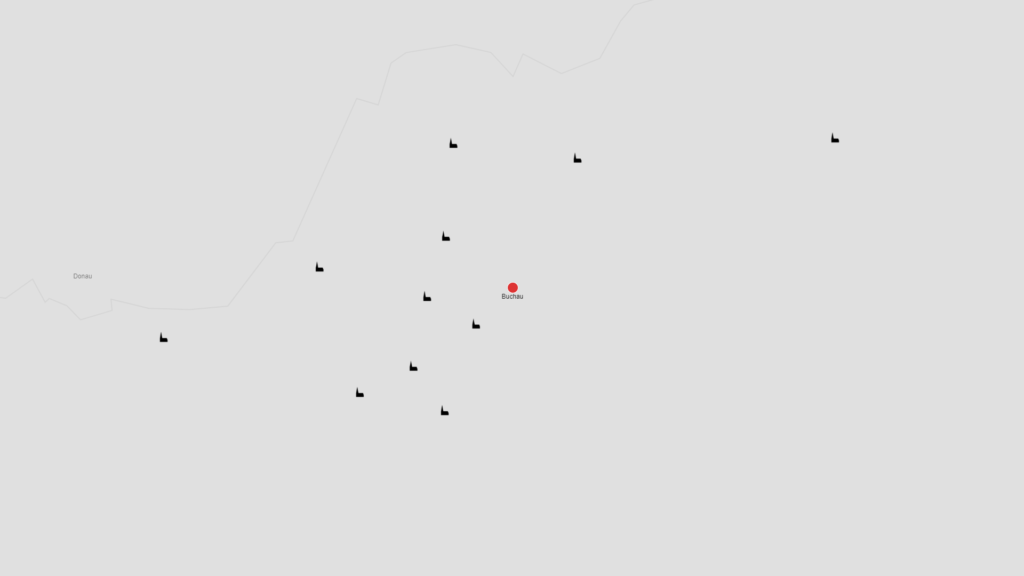

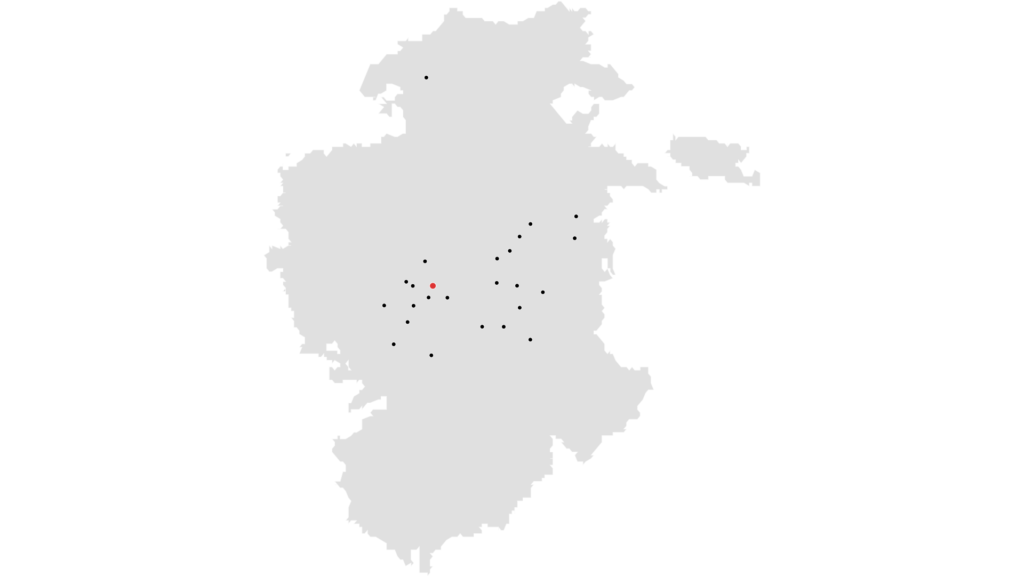

The upper map shows Klingental’s possessions in the 13th century and the lower map in the 14th century. The two maps clearly show as to how much Klingental’s property increased over the course of a century.

- Klingental

- Zehnte

- Grundbesitz und Zinsen