The selected convents are both particularly influential and typical examples of medieval female monasteries. Here, we encounter nuns as city rulers (Fraumünster) and as feudal lords (Notre Dame and Fraumünster). They are impressively able financial managers (Klingental), they regularly sit as judges (Buchau) who have the right to pardon those sentenced to death (Notre Dame). They enjoy authorities as only bishops have in the modern Church. They appointed priests and even convened synods and issued dispensations (Las Huelgas).

Take a closer look at the sample.

Notre-Dame de Soissons

The Secular Power of Brides of God [Benedictines, Abbey, c. 666-1792].

The Beginnings and Territorial Power

Around the year 666, the Frankish mayor Ebroin founded Notre-Dame in Soissons together with his wife, Leuthrude. The couple richly endowed their foundation. As was typical for early medieval monastic foundations, Ebroin was guided by both religious and political motives. Generally, aristocratic founders desired salvation of their souls and hoped to enter heaven more easily. On the political level, monastic foundations tended to strengthen the founder’s local influence. Both factors were also true for Notre-Dame, which was located in the strategically important town of Soissons.

One of the few surviving depictions of the abbey before its destruction. Notre-Dame de Soissons, c. 1800.

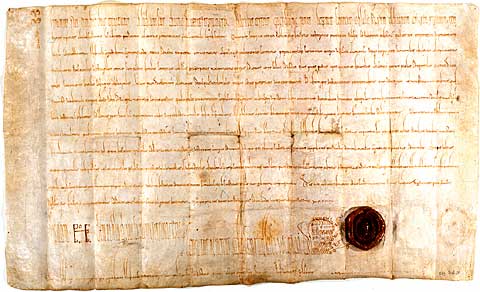

Two charters issued by the French king Charles the Bald tell us that Notre-Dame de Soissons was home to 216 residents in the 9th century. Of these 216 women, 30 were nuns, 40 conversae, i.e. women who had joined the monastery as widows, 16 novices and 130 servants. 216 residents is a very high number for a medieval convent – only Fontevraud had higher numbers. More typical convents were those of Fraumünster which was home to an average of 11 nuns, and also Buchau’s number always remained well under 20.

The two charters also provide information about Notre Dame’s early patrimony. The abbey owned 11 seigneuries, 78 vineyards, 508 farms with serfs, numerous villages and other lands held as fief. While the majority of the abbey’s possessions were in the Soissons region, Notre-Dame also owned lands far away – including seven fiefs in Alsace, 59 farms and a village in the Rhineland.

The Manorial Development in the High and Late Middle Ages

While the many estates and farms made Notre-Dame a very wealthy convent, their wide geographical dissemination presented many challenges. The abbess needed to rely on local administrators to collect the abbey’s revenues – grain, livestock and money. These then had to be transported to the abbey on bad and unsafe roads. Losses along the way were thus inevitable. It was therefore important to eventually cluster the abbey’s patrimony into areas that were closer and more accessible. In the case of Notre-Dame, the eastern possessions were sold after 1164. At the same time, Notre-Dame’s abbesses, especially Odeline de Trachy, began to increasingly buy land around Soissons and steadily enlarged and connected their local seigneuries.

Today, only this wall reminds us of the former size of the abbey. © Wikimedia commons.

Within their seigneuries, the abbess and abbey were the rulers. There, Notre-Dame’s abbess administered justice, levied taxes, appointed priests and provided soldiers for the king’s wars. This seigneurial position was also reflected in a number of building measures at the abbey. As early as the 12th century, an aqueduct brought running water from the Aisne River into the abbey – a luxury that only the richest and most powerful could afford. In the 13th century, a new prison was built inside the abbey, where subjects of Notre-Dames awaited trial. Around the same time, underground tunnels were built that connected the abbey to the city. In the event of a siege, the inhabitants could be supplied, or secretly escape, without opening the gates of the monastery.

Until its dissolution during the French Revolution, Notre-Dame remained an aristocratic and powerful monastery. The life of the nuns always remained marked by both power and religion in equal measure.

AM

Further reading:

A. Müller, Monastic Continuity, Economic Change, and Feudal Society in Later Medieval Europe, Routledge, 2023, chapter 3.

Germain, Histoire de l’abbaye Royale de Notre-Dame de Soissons, Paris 1675.

Cartuaire de Notre-Dame de Soissons, Archives départementales de l’Aisne H 1506.

Buchau

The Abbess-Judges of Buchau [canonesses, around 770-1803].

The Foundation Legend

Various founding legends tell us about the convent’s origins. Current research holds that Adelindis founded the community at Federsee-Lake together with her husband, a Frankish aristocrat, around 770. The foundation of Buchau happened in the greater context of the Frankish conquest of Alemannia. In this context, many new monasteries were founded to help strengthen Frankish dominion and establish the ecclesiastical infrastructure.

Life in Buchau

We know nothing about early religious life at Buchau. However, as of the late Middle Ages, the women at Buchau lived the life typical for canonesses: they did not take perpetual vows – which, in theory would have allowed them to leave the community to get married. However, this rarely ever happened in the Middle Ages. Moreover, they received prebends, i.e. they were paid a salary – and they were free to leave the community for short periods of time, e.g. to visit their families.

Some Men among powerful Women

In addition to the women religious, male clerics also lived in Buchau: The canons. They were in charge of ministering to the community of canonesses. Numerically, there were always less canons than canonesses at Buchau Abbey – about twelve women and three to four men. Both canonesses and canons had seat and voice in the chapter assembly of the Abbey. The chapter was an important political body – among other things, the members of the chapter elected the head of Buchau’s community: the abbess.

Palatinate Judges

Since the 9th century, the abbess of Buchau appointed judges who were allowed to sit court only with her permission. As of the 14th century, we have many documents that testify that the abbess of Buchau herself presided on court days. Everybody who belonged to Buchau in one way or another – whether they were members of the convent, serfs in the service of the abbey, or free peasants living in one of Buchau’s seigneuries – were only allowed to be summoned to appear in court by the abbess herself. The abbatial court was held three times a year.

AS

Further reading:

Bernhard Theil, Das Bistum Konstanz. 4: Das (freiweltliche) Damenstift Buchau am Federsee, Berlin/New York 1994.

Regesten 819 – 1500, bearb. von Rudolf Seigel/Eugen Stemmler/Bernhard Theil, Stuttgart 2009.

Fraumünster

Mistresses of Zurich [Benedictine nuns, abbey, 853-1524].

The First Centuries

In 853, Louis the German (c. 806-876) donated his possessions in the Zurich region to Fraumünster and appointed his daughter Hildegard as abbess. Following the division of the Frankish Empire in the Treaty of Verdun (843), the royal palatinate of Zurich had acquired new strategic importance, as it was both in the border region to the Middle Kingdom and on the Gotthard route to Italy. Louis needed this important region to be in loyal hands, and he therefore entrusted it to the convent his daughter would govern.

During the first centuries, Fraumünster’s abbesses were always recruited from the Carolingian royal family, and the women kept the royal allegiance expected of them. Over the course of the High Middle Ages, the legal authorities of Fraumünster’s abbesses grew continuously. In the mid 11th century, the abbess minted Zurich’s currency, she collected customs on the goods traded in town and she granted the rights to hold market. As of the 13th century, she had the title of Imperial Princess, which gave her the right to sit and vote at the Imperial Diet – a forerunner of a modern parliament which advised the king or emperor on important political decisions.

The abbess was chosen from among the convent – which was only comprised of members of high nobility and which would always remain small in number. On average, only 11 nuns lived in Fraumünster.

Crises and Recovery

The path of Fraumünster Abbey was not a straight one. Between the late 11th and early 13th centuries, the abbess lost much of her political power over Zurich to the dukes of Zähringen. However, with the extinction of the dynasty in 1218, convent and abbess regained power and influence in Zurich. The abbey experienced its peak of power under Elisabeth of Wetzikon (1235-1298).

Decline and Dissolution in the Reformation

The later 14th and especially the 15th centuries witnessed the abbey’s decline – both economically and morally. By the waning Middle Ages, life at Fraumünster had lost most of its former monastic characteristics. The remaining nuns had their own apartments, and the last abbess Katharina of Zimmern (1478-1547) gave birth to a daughter during her abbacy. There was much for the city’s Calvinist reformers to criticize – and they encountered little resistance. In late November 1524, Katharina of Zimmern transferred the convent with all its possessions and rights of rule to the city of Zurich – thus sealing the end of the abbey.

AM

Further reading:

A. Müller, Monastic Continuity, Economic Change, and Feudal Society in Later Medieval Europe, Routledge, 2023, chapter 3.

Niedhäuser / D. Wild (Hg.), Das Fraumünster in Zürich. Von der Königsabtei zur Stadtkirche, Zürich 2012.

J. Steinmann, Die Benediktinerinnenabtei zum Fraumünster und ihr Verhältnis zur Stadt Zürich 853-1524, St. Ottilien 1980.

Fontevraud

A Religious Network under Female Leadership [Fontevrists, Abbey and Order, 1100-1792].

The Beginnings

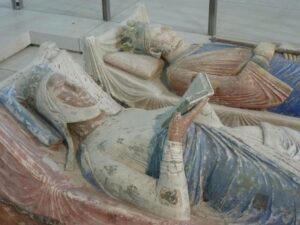

Founded around 1100, Fontevraud was located in Anjou in western France and early on enjoyed great popularity among members of high nobility. Numerous kings of France, but also the illustrious Eleanor of Aquitaine (c. 1122-1204) and her husband Henry II of England (1133-1189), were among the abbey’s most important patrons – and both chose Fontevraud as their burial place.

Inner Structure

Both men and women could and did join the Order of Fontevraud. However, it is more accurate to think of Fontevraud as a women’s order with incorporated male clergy. The male Fontevrists were responsible for the pastoral care of the nuns in the abbey monastery and the order’s many priories. But they also assumed other tasks within the administration. Thus, the order’s archivist, who had to keep track of the thousands of possessions, rights and duties, the visitator, who inspected the order’s individual houses, along with the nun’s confessors were usually recruited from the ranks of the male Fontevrists. Fontevraud’s nuns, who were usually members of French high nobility, dedicated their life to prayer and to administrative matters on site. At the head of the order stood an abbess to whom all Fontevrists owed strict obedience.

Contrary to many other aristocratic monasteries, Fontevraud Abbey reached an enormous size by medieval standards. In 1267, 360 nuns lived in the abbey, which thus had more inhabitants than many contemporary villages. The individual priories were also comparatively large – between 20-50 inhabitants lived in a priory in the 12th century. In the late Middle Ages the numbers decreased somewhat, but even in the 16th century they still averaged about 20 nuns per priory.

Development until the 16th Century

The Fontevrist Order grew rapidly during the 12th century. By 1116, Fontevraud counted 35 priories, and by the 15th century there were at least 78 Fontevrist houses in France alone. Because of the geographical expansion of the Order, whose houses stretched from the Pyrenees in the southwest to Champagne in the northeast, Fontevraud was always politically and strategically important. Whoever had the loyalty of the abbess had political influence on the management of Fontevraud’s territorial possessions.

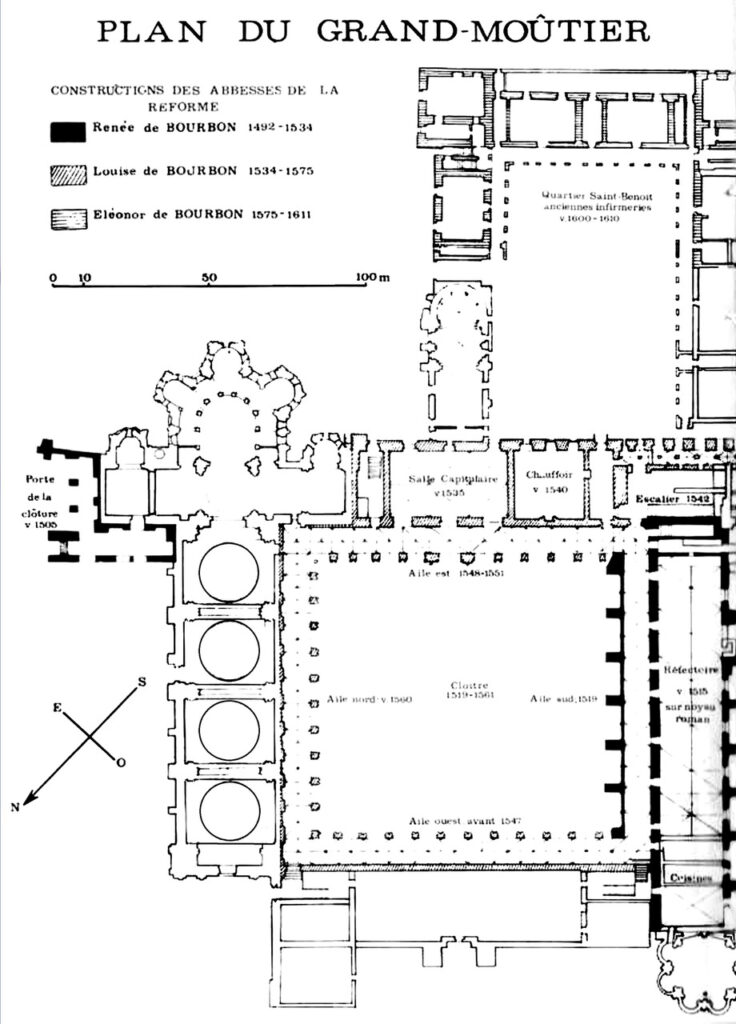

Fontevraud’s geostrategic importance became particularly visible in the late 15th and 16th centuries. At the time, the order’s Bourbon abbesses, who governed the order for five generations, reformed Fontevraud and expanded abbatial authority that henceforth was absolute. Royal loyalty of Fontevraud’s abbesses became particularly important during the French Wars of Religion (1562-1598). At the time, Fontevraud played an important role in affirming royal authority in disputed territories in the south and west of France, and thus helped the kings to eventually win the wars.

AM

Further reading:

Bienvenu, J.-M., L’étonnant fondateur de Fontevraud Robert d’Arbrissel, Paris 1981.

Müller, A., From the Cloister to the State. Fontevraud and the Making of Bourbon France (1642-1100), London 2021.

Las Huelgas

The Bishop’s Rivals [Cistercian nuns, abbey, 1187-present].

Beginnings of Power

The Cistercian abbey of Santa María la Real de Las Huelgas (Burgos, Spain) was founded by King Alfonso VIII of Castile and his wife Eleonor of England in 1187. It was probably modelled on Fontevraud. In 1188, Pope Clement III confirmed the Cistercian rule and the convent’s endowments. Later the same year, the pope decreed that no bishop had any jurisdiction over the abbey.

The Abbesses of Las Huelgas

The abbesses of Las Huelgas were unusually powerful. One of most powerful was Leonor de Mendoza (1486-1499), who is depicted in the painting on the right, protected by the Virgin of Mercy. She is shown with 6 praying nuns and with Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon and the royal family. Contemporaries would recognize in this painting the abbatial claim to worldly power.

And the abbesses of Las Huelgas indeed enjoyed extensive secular power. They were lords over some 60 villages around Burgos, where they acted as judges over both civil and criminal matters. They administered 49 seigneuries with which the convent had been endowed at its foundation. Later, further properties were added, such as a hospital. The ties between Las Huelgas Abbey and the kings of Castile and Leon were close ones. Important ceremonies took place in the abbey: the new king was proclaimed here, and the ceremonial arming of knights.

The Sphere of Power of the Abbesses

The abbess of Las Huelgas was in charge of the 12 Cistercian nunneries in the Kingdom of Leon and Castile. The newly elected abbesses of these nunneries had to travel to Las Huelgas to pledge obedience to the abbess. All other officers of the 12 convents were appointed by the abbess of Las Huelgas, including the prioresses. The abbess of Las Huelgas had further prerogatives: she issued letters of dismissal for priests and allowed candidates to be ordained to the priesthood. She also issued (and revoked) licences authorising priests to hear confessions and preach within the areas under her jurisdiction. Moreover, the abbess was allowed to sanction marriages between partners despite blood relationship and even to convene synods. All these rights were usually reserved for bishops. Not surprisingly, such far-ranging abbatial prerogatives repeatedly raised the envy of local bishops, causing numerous conflicts with the bishops of Burgos. However, the abbesses of Las Huelgas succeeded to maintain most of their rights until the second half of the 19th century. Only in 1874, in the course of a reorganization of the Spanish Church through Pope Pius IX, Las Huelgas was incorporated into the Archbishopric of Burgos.

The Abbey in modern Times

Las Huelgas still is a Cistercian community today. However, unlike her medieval and modern predecessors, the current abbess no longer has any special civil or legal powers or privileges.

AS

Further reading:

Schormann, A., The Ladies of Las Huelgas and Their Political and Spiritual Role, in: Between freedom and submission. The role of women in the history of the Church, (est.) 2023.

Connor, E. (1988), The Royal Abbey of Las Huelgas and the Jurisdiction of its Abbesses IN Cistercian studies, S. 128-155.

Escrivá, J., La Abadesa de las Hulegas, Ed. crític-hístoria, Balaguer 2016.

Klingental

Basel Convent Women with a Sense for Worthwhile Investments [Dominican nuns, later Augustinian choir women, convent, 1236-1557].

The Beginnings

The first community was founded in Hüsern near Pfaffenheim in Alsace in 1236, which Pope Innocent IV incorporated into the Dominican Order in 1246. This early community initially had to overcome some challenges; after all, Hüsern was the site of armed conflicts between the neighbouring town of Rufach to the south and Colmar, 14 km to the north. In 1253, the community moved to a new location in a valley on the Wehra, where the knight Walter of Klingen donated a monastery. In gratitude, the nuns named themselves Klingental after the founder and their geographical location.

But the new location also quickly turned out to be unsafe, because from 1268 onwards, the Bishop of Basel, Heinrich of Neuenburg, and the later German king, Rudolf of Habsburg, fought each other over a nearby castle. In 1274, the nuns therefore decided to move again – this time to Basel, which, as a city, offered some protection from the local wars.

The area of the Klingental monastery (green), the monastery church (violet) and the Kleinbasel city wall from 1278 (grey) shown on the Merian map of 1615.

Edited by: Archäologische Bodenforschung Basel-Stadt.

The Nuns and their Flair for Investment

Even before moving to the city, the Klingentalers acquired strategic estates in Kleinbasel on the left bank of the Rhine – namely three mills and a saw. For in the later Middle Ages, mills in towns were sometimes more valuable than fields in front of towns. For all city dwellers needed milled grain, especially in the densely built-up cities where people could only farm themselves to a limited extent and where they were dependent on the purchase of finished products. Those who had the infrastructure here had a secure, regular income – regardless of crop failures due to war, epidemics or the weather. And owning a saw was another secure source of income in a city where wood was used everywhere and above all for building. Finally, in order to have their own grain, which they could sell on either for their own consumption or, if necessary, ground in their own mills, the women of Klingental bought half of the village of Kleinhünningen as well as various farms in the surrounding area.

From these investment examples it is easy to see that the Klingentaler women were not only very good managers who knew how and where to invest their money sensibly in order to increase it, but also that they were economically at the height of their times. One could also say that they had already acquired a very well-balanced portfolio of central infrastructure and natural resource-producing assets before they moved here. In Basel, the rich Klingental women quickly became a determining economic factor.

Reform, Resistance, Dissolution

The women of the Klingental maintained a lifestyle in keeping with their status and wealth, which led to repeated attempts by the Basel Council in the 15th century to intervene in the life of the convent. In 1480, for example, the convent was to be observantly reformed, an attempt that met with fierce resistance on the part of the Klingentaler women. When members of the council and the Basel reform clergy tried to read the reform bull to the nuns on 8 January 1480, the Klingental nuns made so much noise that the reformers could not be understood. But the reform could not be averted so easily, and five days later thirteen observant Dominican nuns moved into the convent and the Klingental nuns, who were still unwilling to reform, were arrested.

On 28 January, 37 Klingental nuns who were unwilling to reform left their convent and retreated to the old monastery complex in Wehr. From there they litigated against the reform, involving their families and far-reaching political networks. The conflict dragged on for three years, at the end of which the exiles in Wehr prevailed. They returned to Basel and threw the observant nuns out of the convent „with violence that is said to have gone as far as the desecration of the choir“. The Old-Klingental nuns transferred from the Dominican order to the regulated Augustinian choir women and otherwise continued their old life probably quite unchanged.

Like all other Basel convents, the Klingental was dissolved in the course of the Reformation. However, the Klingental nuns resisted this for a long time. While the council had already decided on the dissolution of the convent in 1529 and tried to persuade the nuns to leave the convent with compensation payments, the last nun, Ursula of Fulach, did not leave the convent until 1557.

AM

Further reading:

Gilmon-Schenkel und Degler-Spengler, Basel, Klingental, Helvetia Sacra, Abt. 4, Bd. 2, S. 61-72.

Degler-Spengler und Christ, D. A. Basel, Klingental HS, Abt. 4, Bd. 5 Teil 2, S. 530-583.

Müller, A. Totgesagte leben länger. Das Kloster Klingental als Verwaltungseinheit in der Alten Eidgenossenschaft, in: Hirbodian/ Scheible/ Schormann (Hg.) Konfrontation, Kontinuität und Wandel […], Ostfildern 2022.