Who is Who

Some Interesting Characters

Eterie [Notre-Dame de Soissons, Abbess, middle of the 7th century] - The First One

In the mid-seventh century, the Frankish nobleman, Ebroin, founded Notre-Dame in Soissons and richly endowed it. To ensure that the nascent community would indeed lead a god pleasing life, the bishop of Soissons appointed Eterie as the convent’s first abbess. Prior to her abbatiate, Eterie had been a nun at near-by Jouarre Abbey. Jouarre had been a generation earlier under the influence of St. Columban, and new foundations such as Notre-Dame were modelled upon Jouarre. As is the case with other early abbesses of Notre-Dame, we know no details about Eterie’s abbatiate.

AM

Further reading:

M. Germain, Histoire de L’Abbaye de Notre-Dame de Soissons, 1675, Buch II.

Giselle [Notre-Dame de Soissons, Abbess, c. 780- c.810] - The Emperor's Sister

Giselle was the daughter of Pippin and the sister of Charlemagne. She is said to have come to Notre-Dame at a very young age where she received an extensive education. Approximately in 780, she became abbess and around the year 800, Charlemagne made her abbess also of Chelles, located near Paris. She died in 810.

AM

Further reading:

M. Germain, Histoire de L’Abbaye de Notre-Dame de Soissons, 1675, Buch II.

Richildis [Notre-Dame de Soissons, Abbess, 865- c. 880] - Abbess from a Royal House

As with all early medieval abbesses, we know little about Richilde or her tenure. There are different theories about Richildis‘ origin. She may have been a daughter of Charlemagne or daughters or of Louis the Pious. Whatever her lineage, we may assume that Richildis, like other early abbesses, was of royal descent. Her tenure saw the wars of Charles the Bald in the Soissons region, and the foundation of the chapter of St. Pierre. St. Pierre was a chapter of canons that was subordinated to the abbey and whose members was responsible for the pastoral care of the nuns.

AM

Further reading:

M. Germain, Histoire de L’Abbaye de Notre-Dame de Soissons, 1675, Buch II.

Depiction of Duchess Reginlinde in the parish church of St. Peter and Paul near Lake Zurich. © Wikimedia commons.

Reginlinde - The Duchess [Fraumünster, Abbess 929-958]

Reginlinde was Duchess of Swabia and a member of the court of Otto I. From 929, she was abbess of both Fraumünster and of Säckingen. Moreover, she was one of the founders of the Einsiedeln. Prior to entering the monastic life, Reginlinde had been married to Herman of Swabia. Their daughter, Bertha, married the King of Burgundy, and their granddaughter, Adelheid, rose to empress alongside Otto I.

The Reginline was not only abbess and foundress of monasteries, but also the mother, grandmother and mother-in-law of the powerful persons of the 10th century.

Further reading:

Röthlisberger, J., Reginlinde. Herzogin von Schwaben. Äbtissin des Fraumünsters. Stifterin von Einsiedeln. 885-958.

Pétronille de Chemillé - The Builder [Fontevraud, Abbess 1115-1149]

In 1115, Fontevraud’s founder, Robert of Arbrissel (†1116), appointed Pétronille de Chemillé (†1149) as first abbess. Pétronille, a member of western French nobility, was a very gifted politician who used her family network for the benefit of her community.

After the death of Robert of Arbrissel, Pétronille’s prudent management of both the abbey and the nascent order allowed for the early charismatic congregation to transform into an established institution that was to last for almost seven centuries. Numerous documents from the first half of the 12th century provide information about Pétronille’s activities, especially in western France, where she consolidated Fontevraud’s possessions. Pétronille did not shy away from conflicts with influential bishops and aristocrats – and most of the time, the abbess emerged victorious.

AM

Further reading:

Bienvenu, J.-M., “Le conflit entre Ulger, évêque d’Angers, et Pétronille de Chemillé, abbesse de Fontevrault.” Revue Mabillon LVIII (1972).

Müller, A., From the Cloister to the State. Fontevraud and the Making of Bourbon-France (1642-1100), London: Routledge 2021.

Marsilie [Notre-Dame de Soissons, Abbess, 1162- 4/3/1178] - The Economist

Marsilie was one of the first demonstrably talented economists and politicians. In 1163, the new abbess successfully stood her ground in a conflict with the Bishop of Soissons, whom she made accountable (and repay her) for the murder one of his men committed. On an economic level, she concluded numerous treaties with other abbeys concerning annual dues these had to pay to Notre-Dame.

AM

Further reading:

M. Germain, Histoire de L’Abbaye de Notre-Dame de Soissons, 1675, Buch II.

Julienne [Notre-Dame de Soissons, Abbess, 1179-1186] - The Builder

Under Julienne, the nuns of Notre-Dame received a great luxury: from 1184 onwards, an aqueduct brought running water directly from the Aisne River inside the abbey. In the Middle Ages, this was a rare comfort and only exceptionally rich convents such as Notre-Dame could afford to build and maintain such a building.

AM

Further reading:

M. Germain, Histoire de L’Abbaye de Notre-Dame de Soissons, 1675, Buch II.

Helvide de Cherisy [Notre-Dame de Soissons, Abbess, 1189- 31/01/1217] - The Economist II

Helvide de Cherisy was certainly one of the best economists at the head of the abbey. During her administration, embezzled revenues were returned to the abbey, and the abbey’s rule over its seigneuries was strengthened. Moreover, Helvide’s close ties to the Bishop of Soissons, who was her uncle, helped ensured that conflicts with regional nobles or the city were usually resolved in her favor.

AM

Further reading:

M. Germain, Histoire de L’Abbaye de Notre-Dame de Soissons, 1675, Buch II.

Sancha Garcia - The Priestess [Las Huelgas, Abbess 1205-1230]

Prior to her election as abbess of Las Huelgas in 1205, Sancha Garcia had held the office of cantor for almost twenty years. As cantor, she directed the nuns’ choir, which played an important role in the service, among other things. Perhaps it was her experience as cantor that led her to perform liturgical and sacramental acts afterward as abbess. From a letter of Pope Innocent III in 1210, we know that the pope was concerned about certain practices in Las Huelgas. Sancha Garcia seems to have heard the nuns’ confessions, granted them absolution, and preached the Gospel in public. These were liturgical acts and as such they were reserved for priests – women were expressly not allowed to perform them. While the pope ordered Sancha to stop all liturgical acts, he confirmed the rights of the abbesses of Las Huelgas to exercise their quasi-episcopal jurisdiction.

AS

Further reading:

D’Emilio, J., The Royal Convent of Las Huelgas: Dynastic Politics, Religious Reform and Artistic Change in Medieval Castile, in: Studies in Cistercian Art and Architecture, Kalamazoo 2005, S. 191-282.

Beatrix de Cherisy [Notre-Dame de Soissons, Abbess, 1217 - 24.3.1236] - Defender of Prerpgatives

Beatrix (or Beatrice) was either the sister or niece of her predecessor, Helvide. And like her relative, also Beatrix was one of Notre-Dame’s great 13th -century abbesses. Through extensive economic and territorial reforms, Beatrix laid the foundation for the abbey’s lasting power well into modern times. Like Helvide, Beatrix benefited from her close kinship to the Bishop of Soissons. In this case, the bishop was Jacques de Bazoches, nephew of the abbess. The bishop supported Beatrix in a fierce conflict with the canons of the cathedral chapter of St. Gervais.

AM

Further reading:

M. Germain, Histoire de L’Abbaye de Notre-Dame de Soissons, 1675, Buch II.

Judenta von Hagenbuch - The First Imperial Princess [Fraumünster, Abbess, 1229-1254]

We know little about Judenta von Hagebnuch before she became abbess. She came from a Thurgau baronial family. In 1229, sources mention her as abbess of Fraumünster.

Judenta von Hagenbuch was the first of Fraumünster’s abbesses to hold the title of Imperial Princess. King Henry VII addressed her as such in a charter dated 6 October 1234. Being an imperial princess meant that the abbess was only subordinate to the king or emperor and thus protected from the legal claims of anybody else.

In 1247, Judenta obtained a charter of protection and freedom from Pope Innocent IV. Among other things, the pope forbade the nuns to absent themselves from the convent without abbatial permission. Furthermore, the Pope confirmed the Rule of Benedict for the community. Judenta of Hagenbuch was abbess of the Fraumünster until her death on 14 September 1254.

AS

Further reading:

Wyss, G. von, Geschichte der Abtei Zürich. Beilagen; Urkunden nebst Siegeltafeln, Zürich 1851/58.

Weibel, A., „Hagenbuch, Judenta von“, in: Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz (HLS), Version vom 05.02.2004. Online: https://hls-dhs-dss.ch/de/articles/012664/2004-02-05/, zuletzt Aufgerufen am 03.08.2021.

Odeline de Trachy - The Strategist [Notre Dame de Soissons, Abbess, 1256-1273]

Odeline de Trachy became abbess of Notre-Dame in Soissons in 1256. The 13th century was a difficult period for the abbey. The bishops of Soissons tried time and again to expand their authority over the exempt abbey. The same is true for the canons of St. Pierre, who were responsible for the nuns’ pastoral care. Their desires were understandable, as Notre-Dame owned extensive territorial possessions, with hundreds of serfs and many tax-paying residents. The local prelates would have been only too happy to get their hands on the abbey’s revenues.

Odeline de Trachy proved to be a skilful diplomat and far-sighted politician. With the help of changing alliances, Odeline succeeded to keep the canons of St. Pierre in check. The canons had long tried to blackmail the convent by denying the nuns’ mass in order to obtain additional prebends. In 1273, the conflict was eventually settled in favour of Notre-Dames. The canons had to be content with their traditional reimbursement and if they dared to rebel again, Notre-Dame’s abbess had the right to withdraw their benefices altogether. Odeline de Trachy was also a successful territorial politician. She bought and exchanged territories, forests, fields and roads – thus connecting the abbey’s numerous territorial possessions to form relatively connected clusters. Topography of Power.

After 17 years in office, Odeline retired from the abbacy and spent the last years of her life as a simple nun in Notre-Dame.

AM

Further reading:

Germain, M., Histoire de l’Abbaye Royale de Notre-Dame de Soissons, Paris 1675.

Grand Cartulaire de Notre-Dame de Soissons, Archives départementales de l’Aisne, H 1508, 15.-18. Jh.

Elisabeth von Wetzikon - Imperial Princess and City Mistress [Fraumünster, Abbess, 1269-1298]

Elisabeth of Wetzikon was born around 1235 as the daughter of Baron Ulrich of Wetzikon and a baroness of Kempten. She is first documented as a nun at Fraumünster in 1265. In 1269, Elisabeth of Wetzikon only received half of the votes in the abbatial election. Because of the draw, the final decision was made by the bishop of Constance who appointed Elisabeth.

Despite her external appointment, Elisabeth of Wetzikon was to become one of the most powerful abbesses of Fraumünster. She was an avid builder. During her abbacy, the transept of the church was renewed, and she had a new tomb erected for Fraumünster’s first two abbesses, Hildegard and Berta, who had been the daughters of King Louis the German. In doing so, she placed herself in their direct lineage – a claim to power which contemporaries easily recognized as such. Elisabeth also had the cathedral square enlarged which allowed for a bigger stage for royal visits to Zurich.

Elisabeth’s architectural claims to power were justified. As abbess of Fraumünster, she was an Imperial Princess, and as such, she had seat and voice in the Imperial Diet, the king’s advisory body comprised of the realm’s most powerful. And, of course, she was the mistress of the city of Zurich. In this capacity, the abbess determined and levied custom on the goods traded in Zurich, she granted the right to hold market, she also determined the town’s weights and measures, and she held the right to mint coins, appoint the mint masters and had pennies struck with her portrait.

Elisabeth of Wetzikon died in 1298, after 28 years on the abbatial throne. She was laid to rest next to the two foundresses, in whose tradition of rule she had presented herself during her lifetime.

AS

Further reading:

Steinmann, J., Die Benediktinerinnenabtei zum Fraumünster und ihr Verhältnis zur Stadt Zürich 853-1524, St. Ottilien 1980.

Wild, D., Zürichs Münsterhof – ein städtischer Platz des 13. Jahrhunderts? Überlegungen zum Thema «Stadtgestalt und Öffentlichkeit» im mittelalterlichen Zürich, Zürich 2011.

Infanta Blanca - The Lady of Las Huelgas [Las Huelgas, Señora, 1295-1321]

Blanca was the daughter of King Alfonso III of Portugal and Beatrix of Castile. Following her father’s wishes, Blanca joined the community of Las Huelgas where she came to hold the position of señora. The position of señora was exclusively exercised by an infanta, i.e., a royal princess. While not an official monastic office, the señora was very powerful. Appointed by the king, she acted as mediator between the court (king) and the abbey (abbess). Through her close family ties to the ruling king, she was able to intervene quickly if necessary and ensure the protection of monastic privileges.

In 1295, Blanca became the first señora of Las Huelgas in ten years. And Blanca frequently used her influence in favour of the abbey. During her tenure, she had all the privileges of the abbey newly confirmed by Ferdinand IV. Generally speaking, the señora of Las Huelgas was the guarantor of Las Huelga’s freedom and privileges.

AS

Further reading:

Escrivá, J. M., La abadesa de las Huelgas, Madrid 1944.

Reglero de la Fuente, C. M., Las „Señoras“ de las Huelgas de Burgos: infantas, monjas y encomenderas, 2016, URL: http://journals.openedition.org/e-spania/25542, zuletzt Aufgerufen am 16.08.2021.

Marguerite de Canmenchon [Notre-Dame de Soissons, Abbess, 1296- 1/11/1309] - The Networker

Marguerite de Canmenchon’s abbacy was marked by conflicts with the bishop of Soissons, whom, at the time, tried to extend his authority over the traditionally exempt abbey. Marguerite appealed to the pope and to the other female convents located within the ecclesiastical province of Reims. Together, the convents formed a faction against the bishop. In addition to successfully defending the abbey’s spiritual rights against the bishop, Marguerite also increased Notre-Dame’s secular possessions. Thus, she acquired the vicomtés of Vaux, Mercin and Saconin.

AM

Further reading:

M. Germain, Histoire de L’Abbaye de Notre-Dame de Soissons, 1675, Buch II.

Elisabeth I de Châtillon [Notre-Dame de Soissons, Abbess, 1328- 28/4/1363] - The Crisis Manager

The first source we have of Elizabeth I dates from 1330. At the time, the abbess sent a novice back to her parents due to epileptic seizures which made her physically unfit for monastic life.

Most of Elisabeth’s abbacy was marked by crises, namely the early stages of what would come to be known as the Hundred Years‘ War (1337-1454) and the great plague epidemic (1346-1353). In 1339, Elisabeth succeeded in freeing the abbey from the obligation to provide soldiers for the king’s army. Three years later, the abbess had an underground tunnel built that allowed for secret escapes from the cloister in the case of a city-siege. It is possible that this construction was tied to the early stages of the Hundred Years‘ War, in which Soissons would come to see a great many catastrophes. In the face of these crises, Elizabeth I succeeded to preserve abbey’s wealth and the nuns’ security.

AM

Further reading:

M. Germain, Histoire de L’Abbaye de Notre-Dame de Soissons, 1675, Buch II.

Fides von Klingen -The Crisis Manager [Fraumünster, Abbess, 1340-1358]

In 1340, the convent of Fraumünster could not agree on an abbess. The convent elected two women – Fides of Klingen and Beatrix of Wolhusen. The sede vacante lasted for more than year. In December 1341, Emperor Louis IV intervened and appointed Fides of Klingen.

The period of Fides’ abbacy was a period of economic hardship for Fraumünster Abbey. The plague epidemic (1348) and the recurrent sieges of Zurich by Habsburg troops in the 1350s brought further challenges. To meet the abbey’s financial obligations, Fides sold parts of the abbey’s possessions. While such sales brought short-term relief, they also brought long-term problems, as the alienation of land also meant the loss of the regular revenues that the abbey used to receive from them. When Fides of Klingen died in 1358, her former rival for the abbacy, Beatrix von Wolhusen, was unanimously elected as her successor.

AS

Further reading:

Meyer, A., Klingen, Fides von, IN: Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz (HLS), Version vom 20.08.2007, URL: https://hls-dhs-dss.ch/de/articles/012737/2007-08-20/ (Zuletzt aufgerufen am 28.09.2021).

Wyss, G. von, Geschichte der Abtei Zürich. Beilagen; Urkunden nebst Siegeltafeln, Zürich 1851/58.

Beatrix von Wolhusen – The Abbess and the Thieves [Fraumünster, Abbess 1358-1398].

Beatrix von Wolhusen was consecrated abbess on Palm Sunday 1358 by the vicar general of the bishop of Constance. Beatrix’ tenure was marked by the continuous financial difficulties of Fraumünster and by her monastic community who opposed any financial restrictions – and who did not shy away from theft. In 1373, Beatrix sent an envoy to the episcopal court in Constance. The courier carried the abbey’s annual tax of 50 Gulden. Between Zurich and Winterthur, three armed men attacked the envoy and stole the money. As was later revealed, two sisters and nuns of Fraumünster, Benignose and Benedikta von Bechburg, were behind the attack – they had informed their brother, Johannes, who then robbed the convoy. This incident notwithstanding, Benedikta von Bechburg would eventually become abbess of Fraumünster in 1404.

In 1397, Beatrix who was almost 90 years old, once more had to face a major conflict. At the time, the abbey’s financial problems had reached such proportions that the abbess cut her nuns’ prebends. This caused the nuns to turn against their abbess and to ask Zurich’s city council for support. Presumably because of her old age and the lack of support from her convent, Beatrix accepted retirement and allowed the council to appoint three administrators to reform the abbey’s finances.

AS

Further reading:

Wyss, G. von, Geschichte der Abtei Zürich. Beilagen; Urkunden nebst Siegeltafeln, Zürich 1851/58.

Feller-Vest, V., „Wolhusen, Beatrix von“, in: Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz (HLS), Version vom 20.11.2013. Online: https://hls-dhs-dss.ch/de/articles/013068/2013-11-20/, zuletzt Aufgerufen am 10.12.2021.

Anna von Rüssegg - The Abbess and her Parliament [Buchau, Abbess, 1371-1402].

We know little about Anna’s family background. She was elected abbess of Buchau on 25 July 1371. In September of the same year, the bishop of Conastance confirmed Anna von Rüssegg as abbess of Buchau.

During Anna von Rüssegg’s abbacy, a major conflict between the abbess and her chapter ultimately endowed the chapter with greater power. The àchapter comprised the canonesses and canons of the Buchau – it was a sort of parliament, whose actual rights had traditionally been limited. In 1381 the chapter of Buchau accused Anna von Rüsseg of leasing parts of Buchau’s property without obtaining the chapter’s consent. To resolve this dispute, seven external arbitrators came to Buchau. They eventually decreed that in future matters of selling or leasing, all decisions had to be made jointly by chapter and abbess. In the same year, the abbey thus obtained a further political body that henceforth introduced some checks and balances into Buchau’s cloister.

AS

Further reading:

Theil, B., Das Bistum Konstanz. 4: Das (freiweltliche) Damenstift Buchau am Federsee, Berlin/New York 1994.

Regesten 819 – 1500, bearb. von Seigel, R./Stemmler, E./Theil, B., Stuttgart 2009.

Elisabeth II de Châtillon [Notre-Dame de Soissons, Abbess, 1392-1429] - The Protector

Elisabeth II was the great-niece of Elisabeth I de Châtillon. Also the abbacy of Elizabeth II was marked by the Hundred Years War, and especially the siege of Soissons in 1414, when the Burgundians (allied with England) fought about Soissons with the King of France. In the years that followed, Elizabeth II devoted herself above all to the reconstruction of the abbey’s farms and properties outside the city walls, which the wars had destroyed.

AM

Further reading:

M. Germain, Histoire de L’Abbaye de Notre-Dame de Soissons, 1675, Buch II.

Engeltrut and Anna von Eptingen – A Family Affair [Klingental, nun/prioress, before 1401- after 1430].

We know little about the individual nuns and prioresses of Klingental. This is also true for Engeltrut von Eptingen. She joined the convent before 1401 and we know that she served as prioress in 1426. Sources mention her again in 1430, however, this time as a regular nun rather than prioress. Her relative, Anna, was also a nun at Klingental. Anna is first mentioned in 1366, however, we know nothing certain about the offices she held.

The Eptingen family belonged to Basel’s most influential families. And as such, they would naturally make it possible for select female relatives to enter such a prestigious convent as Klingental. It seems like a number of Eptingen nuns were living in Klingental around that time. In 1382, Katharina Schalerin, wife of Johann von Eptingen, made a gift to the monastery with special reference to her five daughters living there. All in all, the Eptinger family richly endowed Klingental both with daughters and possessions.

AS

Further reading:

Staatsarchiv des Kanton Basel-Stadt Klingental Nr. 1453, 1107, 1809, 1852, 1630, 1772.

Agnes von Tengen - A Typical Abbess of Buchau [Buchau, Abbess, 1410-1426].

The Tengen family rose to the ranks of counts in the 15th century. Agnes von Tengen was a close relative of Anna von Rüssegg, who had governed Buchau from 1371-1401. Prior to her election as abbess, Agnes of Tengen appears twice in Buchau’s documented sources as a choir woman in Buchau in 1408. On 24 February 1410, she was elected abbess.During her abbacy, Anna donated an annual revenue from wine sales that was to be used to celebrate an annual mass after her death. Such anniversaries were common and meant to commemorate the deceased.

AS

Further reading:

Regesten 819 – 1500, bearb. von Seigel, R./Stemmler, E./Theil, B., Stuttgart 2009.

Schormann, A., Gott zu lob und den seelen die ir almusen her geben habenndt zu trost unnd hilf […] Stiftisches Leben in Oberschwaben, in: Zwischen Mittelalter und Reformation. Religiöses Leben in Oberschwaben um 1500, S. 15-27.

Klara von Montfort / Clare of Montfort - The Count's Daughter [Buchau, Abbess, 1426-1449].

Klara von Montfort is first mentioned as canoness in Buchau in 1419. She was born into a local comital family. Elected abbess in late 1426, the bishop of Constance confirmed her election in January 1427. As new abbess, Klara von Montfort took an oath on 16 articles that regulated her abbatial authorities. She was to reside in Buchau at all times. Moreover, she was not allowed to alienate convent property without the chapter’s consent. Abbatial power was not absolute in Buchau – and Klara needed the votes of the abbey’s other residents in important decisions.

Klara governed Buchau jointly with the chapter until 1449. At this point, worn out by old age and illness, she chose to resign from her office. However, before she retired, Klara succeeded to have her relative, Margaret of Werdenberg, who was still a minor at the time, elected as her successor.

AS

Further reading:

Theil, B., Das Bistum Konstanz. 4: Das (freiweltliche) Damenstift Buchau am Federsee, Berlin/New York 1994.

Regesten 819 – 1500, bearb. von Seigel, R./Stemmler, E./Theil, B., Stuttgart 2009.

Johann von Eschenberg – An energetic Administrator [Klingental, Schaffner 1443-1467].]

Johann von Eschenberg served as schaffner in Klingental. The office of schaffner was an important one. He was present at the economic accounting of the prioress, the female schaffner, and the sisters. He administered part of the convent property, represented the economic interests of the convent to the outside world and, if necessary, went to court on behalf of the nuns.

Johann von Eschenberg is the best-known schaffner of Klingental. Prior to being appointed schaffner, he served as census master, i.e. he was responsible for the collection of the monastery’s dues. When Klingental’s old schaffner died, Johann was appointed his successor in 1443. Johann was responsible for a number of administrative reforms. Thus, household books were introduced during his tenure that recorded both the income and the expenditure of the convent. Johann also set standards in other areas. He supervised Klingental’s Kornhaus (granary), which was the convent’s central storage unit for grain and other natural goods. Those rents paid in grain were collected and recorded by the granary, asit was one of the monastery’s central economic pillars. Under Johann’s leadership, the granary made a profit for the first time. However, generally the granary was administered by a nun, the kornhausmeisterin (granary mistress). Johann von Escheneberg would remain the only male Schaffner in charge of Klingental’s granary.

AS

Further reading:

Weis-Müller, R., Die Reform des Klosters Klingental und ihr Personenkreis, Basel 1956.

Clara zu Rhein - The Family Placement [Klingental, Prioress, 1447-1452]

Rather than elected for life, the prioresses of Klingental generally served three-year tenures. Because of the frequent changes, it is difficult for historians to trace who governed the community at a given time.

Clara and her sister Agnes joined the community of Klingental probably at a young age, sometime before 1412. In 1447, Clara was elected prioress, a term she exercised for three years. The zu Rhein family belonged to Basel’s most influential families and they made sure to place their children into influential positions within powerful institutions. Clara’s brother Friedrich was Prince-Bishop of Basel from 1437. Another sister, Ursel zu Rhein, was head of Heiligkreuz monastery in Alsace.

Like her family, Clara was also generous. Throughout her life at Klingental, she donated altarpieces, books and a monstrance to the monastery. After her tenure as prioress ended, Clara continued her life as a nun until her death on 27 November 1455.

AS

Further reading:

Gilomen-Schenkel, E., „Zu Rhein, Clara“, in: Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz (HLS), Version vom 24.02.2014. Online: https://hls-dhs-dss.ch/de/articles/026595/2014-02-24/, zuletzt Aufgerufen am 13.08.2021.

Weis-Müller, R., Die Reform des Klosters Klingental und ihr Personenkreis, Basel 1956.

Margarete von Werdenberg - The Young Abbess [Buchau, Abbess, 1449-1496].

Margarete von Werdenberg was the successor of Klara von Montfort. Margarete came to the abbacy at the young age of twelve. Because of her young age, she needed to obtain a special privilege from Pope Nicholas V. It is more than likely that Margaret’s family had a hand in this. Her mother was Elisabeth of Württemberg, who probably used her family connections to persuade the Counts of Württemberg and the city of Ulm to appeal to the Pope. For the first decade or so of her abbatiate, she did not govern alone – deemed too young for the task.

Many sources testify to Margarete von Werdenberg acting as judge as an adult. The trials she presided over were mainly concerned with economic matters. For example, Margarete presided over the trial between the abbess Heggbach, Elisabeth Kröll, and Wilhelm Wielen of Winnenden, who fought over fiefs in several villages, which were then divided up by Margarete in 1467. As abbess, Margarete of Werdenberg was also able to pardon prisoners in the towns of Buchau and Saulgau.

AS

Further reading:

Theil, B., Das Bistum Konstanz. 4: Das (freiweltliche) Damenstift Buchau am Federsee, Berlin/New York 1994.

Regesten 819 – 1500, bearb. von Seigel, R./Stemmler, E./Theil, B., Stuttgart 2009.

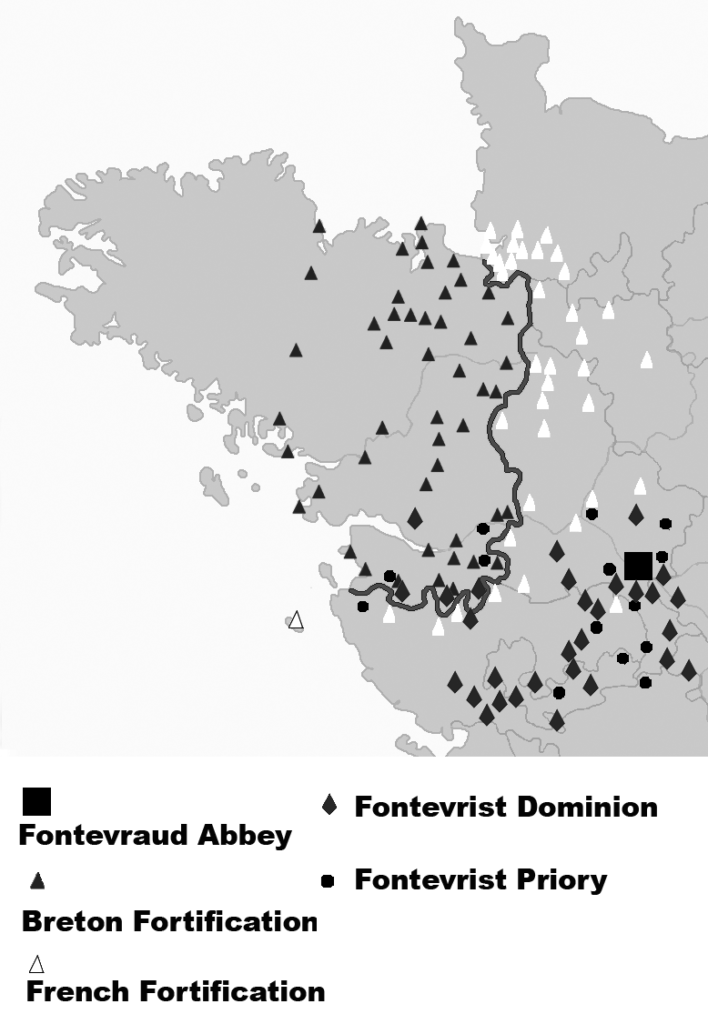

Marie de Bretagne - Reforming Abbess [Fontevraud, Abbess, 1457-1477].

Marie de Bretagne, sister of the last Duke of independent Brittany, François, was appointed Abbess of Fontevraud in 1457. When she took up her abbacy, Marie de Bretagne was not yet an ordained nun – she only took the veil on the day of her consecration as abbess.

Under Marie’s abbacy, the complicated process of Fontevraud’s long reform began (c.1457-c. 1575). The intended reform was both structural and religious. A structural reform was needed as the Hundred Years’ War (1337-1453) had inflicted great damage on many Fontevrist priories. Shortly after her appointment, the new abbess sent her prior, Guillaume de Bailleul, to inspect all Fontevrist houses and compile an economic and personnel inventory. Meanwhile at the abbey, Marie prepared a comprehensive religious reform. A new rule was to standardize religious life in the abbey and Fontevraud’s 78 priories and, most importantly, restore monastic discipline. However, Fontevraud’s community did not take kindly to the plans of reform.

Due to the fierce opposition at the abbey, Marie and a small entourage retreated to a Fontevrist priory near Orléans in 1471. Here, Guillaume de Bailleul wrote a new rule for the entire Order, which Sixtus IV approved in 1476. Over the course of the following century, the so-called Rule of Marie de Bretagne was gradually introduced into all Fontevrist houses – often by use of force, as local Fontevrists generally rejected the stricter way of life the rule envisioned. However, Marie de Bretagne was not to see this process. She died in 1477 in Orléans without ever having returned to the abbey.

AM

Further reading:

Müller, A.: From the Cloister to the State. Fontevraud and the Making of Bourbon France (1642-1100), London: Routledge, 2021, S. 92-97; 131-144.

Guillaume de Bailleul († after 1480), Fontevrist - The Invisible Reformer

Unfortunately, we know little for certain about Guillaume de Bailleul, although he was a central figure in Fontevraud’s early reform (1457-1480). Under Marie de Bretagne, Guillaume served as prior of Saint Jean de l’Habit, Fontevraud’s male priory. This position made Guillaume the most important male Fontevrist. In 1459, Guillaume travelled to inspect over 50 Fontevrist priories, mainly in western and southern France. He produced an extensive economic report which included the annual income of each priory, the number of male and female residents, and the condition of the buildings.

After his return to Fontevraud Abbey, he presumably played an important role in the first attempt at religious reform, which, however, failed due to the resistance of the abbey’s residents. In 1471, he left Fontevraud together with àMarie de Bretagne to advance the order’s reform from outside the recalcitrant abbey. It was very likely that Guillaume was the primary author of Fontevraud’s new rule compiled in exile in Orléans.

Prior to Fontevraud’s 15th and 16th– century reform, Fontevrists had lived by a mixture of rules: in addition to a series of statutes left by Fontevraud’s founder, Robert of Arbrissel, the men followed the àRule of Augustine and the women the àRule of Benedict. With the reform, a single rule was then to structure the lives of both male and female Fontevrists. While Sixtus IV approved the new rule in 1476, it would take most of the 16th century to actually get the Fontevrists to accept life according to the reformed rule. Guillaume de Bailleul did not live to see the eventual success of his efforts. He probably died during the 1480s.

AM

Further reading:

Müller, A.: From the Cloister to the State. Fontevraud and the Making of Bourbon France (1642-1100), London: Routledge, 2021, S. 133-144.

Leonor de Mendoza - The Combative [Las Huelgas, Abbess, 1486-1499]

Diego de la Cruz, The Virgin of Mercy with the Catholic Monarchs and their family. On the far left, dressed in red, Leonor’s brother, Pedro Gonzáles de Mendoza. In detail, the nuns of Las Huelgas with their abbess in the front: Leonor de Mendoza.

Leonor de Mendoza was one of the many powerful abbesses of àLas Huelgas. Her family, the House of Mendoza, belonged to the most powerful within Spanish nobility. Among the many high state and ecclesiastical offices, held by the Mendozas between the 14th and the 17th centuries, was the abbacy of Las Huelgas through Leonor and the cardinalship of her brother, Pedro González.

During Leonor’s abbacy, the bishop of Segovia arrogated authority over several monasteries traditionally under Las Huelgas’ authority. There, the bishop deposed the ruling abbesses and replaced them with women loyal to him.

Naturally, Leonor could not accept such interference and she turned to Pope Innocent VIII for help. She argued that the convents in questions were dependent on Las Huelgas and that only the abbess of Las Huelgas had the right to confirm the election of local abbesses. Innocent VIII appointed a papal delegation to investigate the matter. The delegation found that indeed the bishop of Segovia had acted illegally. They restored to the abbess of Las Huelgas her lawful rights. Once again, an abbess of Las Huelgas had succeeded to defend her rights from attempts of arrogation by a local bishop.

Further reading:

Rodriguez López, A., El Real Monasterio de Las Huelgas de Burgos y el Hospital del Rey, Burgos 1907.

AS

Renée de Bourbon - The Iron Lady [Fonetvraud, Abbess, 1491-1534].

Renée de Bourbon became abbess of Fontevraud in 1491. While the circumstances of her election or appointment are unknown, Renée was to become one of the order’s most important abbesses and the first of five Bourbon abbesses who governed Fontevraud between 1491 to 1670.

Although the name of the Fontevrist reform is linked to Marie de Bretagne, it was Renée who was largely responsible for its successful implementation. From 1496 on, she began to prepare the reform of Fontevraud-Abbey, which had hitherto rejected to embrace reform. Resistance at the abbey continued and the reform process took two years (1504-1506) and, in the end, required the use of force. Thus, Renée sought the help of her brother’s armed men to evict rebellious monks from the abbey. Her willingness to use violence to achieve her ends notwithstanding, Renée herself was a devout believer in the reform, and in June 1504, she became the first Fontevrist abbess ever to take the vow of enclosure.

With the help of her family network and the support of those nuns and monks loyal to her and the reform, Renée de Bourbon reformed priory after priory. In the process, the local Fontevrists had to choose between renewing their vows according to the reformed rule or leaving the monastery. The reformed rule brought a number of changes to Fontevrist life. The order’s nuns had to accept enclosure and Fontevrist office holders, such as prioresses and confessors, the limitations of their tenure to three years. Of all Fontevrist offices, only the abbacy continued to be held for life. This discrepancy brought a significant gain of abbatial power at the expense of all other office-holders, and led to fierce conflicts within the order. However, this new Fontevrist structure was repeatedly confirmed by the Parlement de Paris (e.g. in 1520).

Renée de Bourbon died in November 1534, having previously appointed her niece, Louise, whom she had raised, as her successor. Louise de Bourbon (1534-1575) continued her aunt’s work – she completed the Order’s reform and consolidated abbatial authority which reached a new dimension with the reform.

AM

Portrait of Renée de Bourbon in the chapter house of Fontevraud Abbey. © ARCHIVE NUMÉRIQUE DE LA COLLECTION GAIGNIÈRES (1642-1715).

Further reading:

Müller, A.: From the Cloister to the State. Fontevraud and the Making of Bourbon France (1642-1100), London: Routledge, 2021, S. 152-172.

Katharina von Zimmern – The Last Abbess [Fraumünster, Abbess, 1496-1524].

Panelling of the abbess's room of Katharina von Zimmern in the Fraumünster in Zurich, with coats of arms of Zimmern and of Oettingen. © Wikimedia commons.

Katharina von Zimmern was born in Upper Swabia in 1478. Together with her sister, Anna, she joined Fraumünster Abbey in 1491. Five years later, Katharina was elected abbess at the age of 18 years. She was to hold the office for 28 years. While Fraumünster had lost many of its traditional prerogatives to the city of Zurich, its abbess still held the title and status of Imperial Princess and was, at least nominally, the city ruler of Zurich. And Katharina knew how to act the part. During her tenure, she had the abbess’s courtyard rebuilt, the abbey refurnished, and the abbatial room remodeled. Moreover, the educated abbess maintained close ties to Zurich’s humanist circles and was said to have followed early reformatory debates with great interest. However, when Zurich’s reformer, Huldrych Zwingli, demanded the dissolution of all monasteries in 1523 onwards, the abbess of Fraumünster began to feel the pressure.

Zwingli’s fundamental criticism of monastic life hit close to home at Fraumünster. At the time, the convent comprised no more than four or five nuns who enjoyed a pompous rather than ascetic lifestyle. They lived in individual flats and enjoyed an upscale and, above all, worldly lifestyle. This also applied to the abbess who had a daughter during her abbacy. While not desirous to leave the abbey, Katharina von Zimmern eventually had to bow to public pressure. In late November 1524 she agreed to dissolve the abbey and to transfer all its possessions, rights, and revenues to the city council. In return, Katharina obtained burgher rights, free housing and she received a life-long pension from the city which was twice the amount of her annual income as abbess.

AS

Further reading:

Christ-von Wedel, C., Die Äbtissin, der Söldnerführer und ihre Töchter. Katharina von Zimmern im politischen Spannungsfeld der Reformationszeit, Zürich 2019.

Gysel, I., Zürichs letzte Äbtissin Katharina von Zimmern: 1478 – 1547, Zürich 2011.

Cathérine de Hem [Notre-Dame de Soissons, Abbess, 1510-1518] - The Last Independent Abbess

During Cathérine de Hem’ abbacy, Notre-Dame de Soissons effectively came under Fontevraud’s control. In 1518, the fontevrist abbess,Renée de Bourbon, sent 10 of her nuns to Soissons to reform Notre-Dame. The nuns brought with them fontevrist liturgy and cloister life in strict enclosure. With the help of Cardinal Louis de Bourbon, nephew of Fontevraud’s abbess, Cathérine was banished from the convent a short time later and replaced by a fontevrist nun. As of 1518, Notre-Dame was de facto part of the vast fontevrist network.

AM

Further reading:

M. Germain, Histoire de L’Abbaye de Notre-Dame de Soissons, 1675, Buch II.

Ursula von Fulach – Last Woman Standing [Klingental, Choir woman, before 1525- 1557]

When the Reformation was introduced in Basel in 1529, the majority of Klingental’s nuns initially refused to leave their convent. Basel’s city council reluctantly allowed the women to stay, while at the same time the council took over control of Klingental’s possessions. Life at Klingental was thus made increasingly uncomfortable, prompting a number of nuns to eventually leave the cloister. However, seven women remained despite everything, and they were eventually granted the right to live out their lives in the convent. Ursula von Fulach was one of the final seven. Despite pressure from the council, Ursula remained steadfast and loyal to her convent, and she remained committed to the Old Faith throughout her life.

However, the clock worked against the nuns and for the Reformation. By 1556, only two old nuns still lived in Klingental: namely the last abbess, Walpurg von Runs, and Ursula von Fulach. When the abbess died on 10 October 1557, Ursula von Fulach still wanted to remain and insisted that she was Walpurg’s rightful successor. However, alone, she stood no chance. Eventually, she had to accept defeat and left Klingental and Basel around 1560.

AS

Further reading:

Müller, A., Totgesagte leben länger. Das Kloster Klingental als Verwaltungseinheit in der Alten Eidgenossenschaft, in: Konfrontation, Kontinuität und Wandel […], Ostfildern 2022.

Knecht, S., Ausharren oder austreten? Lebenswege ehemaliger Nonnen nach der Klosteraufhebung am Beispiel der Städte Zürich, Bern und Basel, Zürich 2016.

Burckhardt, C./Riggenbach, C., Die Klosterkiche Klingenthal in Basel, Basel 1860.