Economic and Social System

Authority based on Land Ownership

In medieval society, sovereign rights – including jurisdiction, the preservation of public safety, taxation and the coinage of money – were tied to the rule over land. The so-called manorialism formed the basis of power for both the secular and clerical ruling lords and ladies. Medieval structures of power thus differed fundamentally from that of the modern nation-state, in which rule is characterized by the separation of powers and where only the government has the right to levy taxes, mint money, send soldiers to war, etc.

In the Middle Ages, the sovereign rights today exclusively associated with the state not only lay with the king, but also with the landowning, i.e. manorial, nobility, bishops and monasteries, all of whom often owned large estates, also referred to as seigneuries. The people who lived on these lands were subject to the respective seigneur, that is noble or monastery – including peasants who worked the fields, craftsmen and artisans who produced the goods, and even entire towns. They paid taxes to their monastic or secular seigneur, owed war services, and were subject to the jurisdiction of their lord or mistress.

We can thus say there was not one ruler who had a monopoly of authority in the Middle Ages, but, in addition to the king, there were many local rulers who were in charge over territories of very different size and importance.

The so-called Feudal Society

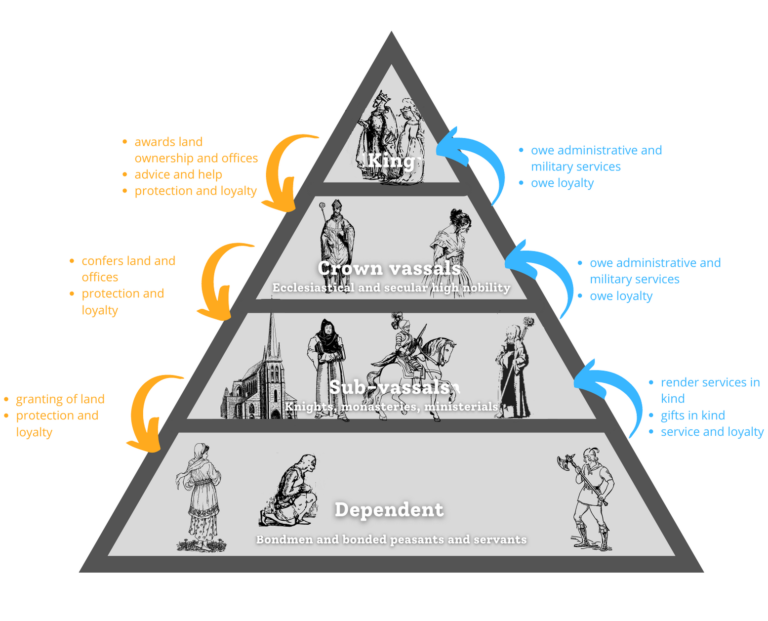

Although there was no state in the modern sense, the medieval political system had a clear hierarchical order. At the top was the king (or emperor), who, at least nominally, also had the largest landholdings. In second place came the high secular and ecclesiastical nobility. These were followed in the social order by the middle and lower nobility, including the knighthood. At the bottom of the pyramid were peasants and craftsmen, who made up about 90% of the population.

The members of the different social categories were bound to each other hierarchical relationships – the so-called feudal system. Simplified, one can say that the feudal system consisted of the granting of manorial land. For example, the king would bestow a piece of land with a forest, a lake, and several villages to a member of nobility. In return, the noble was obliged to provide the king with military services when called up0n, and to pay annual dues. In entering the “deal”, the noble in question became subject to the king – he was his vassal who owed him payment and services. At the same time, however, the king provided him with lucrative land and manorial rights. The noble could then lend parts of the land to others, e.g. to free peasants, also in return for revenues and military service; or the nobleman could administer the land himself and have it worked by the peasants living on it, who gave him part of the harvest in return. Our noble in question could also be a bishop or an abbess. The feudal Middle Ages hierarchy were not strictly male.

The medieval social order can be schematically represented as a pyramid, whose members were strictly hierarchical and separated according to status, but that were bound to each other in economic, military, etc. relationship.

AM

Further reading:

Melville, G./ Staub, M., Enzyklopädie des Mittelalters.

Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz.

Duby, G., Die drei Ordnungen. Das Weltbild des Feudalismus, 1993.

Reynolds, S., Fiefs and Vassals: The Medieval Evidence Reinterpreted, 1994.

Life Paths: Men and Women in the Middle Ages

The Third Estate

The lives boy and girls, men and women could expect to live depended on many factors beyond their individual control. Social standing was the most determining factor. Thus, in rural environments, the young generation usually expected to live a very similar life to that of their parents. The ideal path was the following: generally one got married in one’s 20s and in due course took over the farm of one’s parents. However, reality was often more dire. With the enforcement of primogeniture in the High Middle Ages, i.e. the sole right of inheritance of the eldest son, younger sons could no longer hope to inherit land. As a result, they were increasingly drawn to the emerging cities in order to make a living there.

However, the chances of social advancement in the city were slim, and many male newcomers were forced to eke out an existence as day labourers. Daughters were also able to earn a living in the cities – as maids, for example. But also for them, opportunities were often very limited. Without family protection and if no employment could be found, young girls from the lowest ranks of society often had very few options, and many had to take to prostitution.

The Third Estate was very diverse, as it comprised the fast majority of medieval society. Thus, also the urban bourgeoisie that emerged in the late Middle Ages also belonged to it. Their members often had greater economic means, which also gave them more opportunities such as sending their children to schools or providing them with a sound education in a professional craft in the context of the city’s guilds. Marriages between members burgher families were the norm and were modelled on the practice of the nobility. Women assumed important functions within both merchant and artisan families. They helped in their husbands’ workshops. As widows, they were usually able to continue their husband’s workshop independently for a period of time. Outside of the family unit, women could also act as independent traders – and some even become rich at it. However, most women worked mainly as brewers, in food preparation or in the textile trade. Only very few men and women were able to advance socially and economically.

The Second Estate

Boys and girls who were fortunate enough to be born into the Second Estate usually had the prospect of more material security, but they did not necessarily enjoy more individual choices. Often, their path of life was already predetermined at birth. Thus, the education of the eldest son usually cantered on preparing him to succeed his father as count, duke or even king. Other sons were chosen early for the clerical path at the head of a bishopric or for a knightly career. For daughters, too, the paths were marked out early on. After an education in a monastery or at their parents’ court, they were either married or were chosen for a monastic career in a monastery that was as influential as possible. Often the goal was that at least one of the daughters would become abbess within the monastery (see family politics). In sharp contrast to western societies, medieval society did not allow for individual life planning – and this applied to everybody, regardless of their social standing or gender.

The First Estate

Of the Three Estates, only the clerical estate could be entered (rather than being born into). Members of the First Estate were often recruited from the nobility. However, men and women from the Third Estate could also receive ecclesiastical ordination if they had the financial means to enter a monastery or could afford to study theology at the one of the new universities for their sons. Boys and girls usually joined a monastery at a very young age. The monastery schools provided them with an extensive education and life in the monastery held many opportunities especially for girls and women, that were not open to them in the world.

Further reading:

Hanawalt, B., The Wealth of Wives: Women, Law, and Economy in Late Medieval London, 2007.

Ennen, E., Frauen im Mittelalter, 1993.

Schubert, E., Alltag im Mittelalter. Natürliches Lebensumfeld und menschliches Miteinander, 2002.

Monasteries as Economic Units

Monasteries were places of faith and prayer. But they were also – necessarily – places of economy. In a world where the essentials of every-day life could not simply be bought in convenience stores, most things had to be produced on site. This applied to villages as much as it applied to monasteries. If a monastic institution wanted to survive, they had to produce what they needed. This importance of economic self-sufficiency is also reflected in monastery plans, such as the Plan of St. Gall.

Monastic Ideal and Historical Reality

Since its earliest times, the monastic ideal always advocated for life far removed from society. Monks and nuns ought to live in the metaphorical desert, embracing strict asceticism. They should only eat, drink and sleep the pure minimum required for survival. Monastic ideal advocated the suppression of the bodily needs in order to emulate the martyrdom of Jesus and to concentrate entirely on serving God. These ideals go back to the Desert Fathers and Desert Mothers of the Near East, the first men and women who lived as monks and nuns in the deserts of Syria and Egypt in the 3rd century AD (The Origins).

The ideal to withdraw from the world, and living a life of strict asceticism, remained the ideal of Christian monasticism throughout the Middle Ages. But even for those communities who really sought to live the monastic ideal, this quickly proved difficult in reality. A community needed food and clothing – and no matter how low the fabric or how restrained the diet, these (and other things) had to come from somewhere. While all monastic communities were faced with this challenge, the solutions differed according to time and place. In (early) medieval Europe, the problem was solved through endowments. At the time around its foundation, a community received donations of land that were meant to provide for the community’s sustenance. However, especially in the context of aristocratic communities, the monastery’s economic endowments exceeded the necessary, and many convents were actually rich.

Monastic Economies

Early medieval monastic foundations such as Notre-Dame de Soissons, Buchau, and Fraumünster, but also high medieval ones such as Fontevraud and Las Huelgas, usually received generous donations from their founders as well as local benefactors. For example, Fraumünster, founded by King Louis the German in the nineth century, received not only Zurich, but also many seigneuries located in the modern Swiss cantons of Uri and Schwyz. Notre-Dame de Soissons was also richly endowed. A confirmation of the abbey’s possessions from 858 lists eleven seigneuries, 78 vineyards, 508 farms including serfs, as well as numerous villages and fiefdoms.

Moreover, monasteries usually also owned a number of forests (for wood and hunting), quarries (for building materials), mills (to grind flower) and ponds (fish farming). If a monastery owned more than it needed (which was often the case), it could sell the surplus production in local markets and leasing the use of its mills to local peasants brought the monastery additional income.

In terms of their wealth, there were significant differences between individual monasteries. Notre-Dame and Fraumünster naturally belonged to the very rich institutions – and we may safely assume that their inhabitants did not live a very ascetic lifestyle. However, even institutions such as Notre-Dame and Fraumünster who disposed of such generous endowments frequently faced challenges. Thus, a convent’s seigneuries were sometimes spread across vast regions, they were rarely connected and the infrastructure in the Middle Ages was generally very poor, very much complicating their effective administration – especially in times of war.

Administration

In addition to leading her community in a God pleasing life, one of the central tasks of an abbess was to preserve, and even increase, the community’s patrimony. As one can easily imagine this was not an easy task. The portfolio of monastic possessions was not only heterogeneous, but said possessions often were geographically scattered. Thus, Notre-Dame’s early possessions were partially located more than 100 miles apart. Further, in addition to houses and fields in the city of Soissons itself, Notre-Dame owned farms in the Rhineland, about 200 miles east of Soissons.

To ensure local administration of distant possessions, abbesses appointed local representatives, so-called mayors. They were responsible for collecting the dues of the local peasantry and transferring them to the abbey in fixed intervals. They were also responsible to maintain the peace and thus administered justice. These mayors were themselves subject to the authority of the abbess.

In Buchau, for example, there were 12 Meierhöfe (mayorial manors) which were intermediaries between abbess and peasantry. The mayors not only collected the revenues, but also formed the court of judges to which all subjects of Buchau Abbey were subject.

While local administrators such as mayors managed the monastery’s economy on the local level, all threads tied together in the abbey. There, the management tasks were extensive. The mayors had to be controlled and embezzlement avoided, all revenues received had to be accounted for, and legal conflicts along with the rendered judgements had to be archived. In her far-ranging administrative and governmental duties, the abbess was assisted by a number of officers. These sometimes included a prioress and the cellarer, along with archivists, scribes and other assistants.

Long-term Management

Administrating the patrimony of a monastery was a long-term project. These institutions often existed for a very long time – in the case of Notre-Dame and Buchau, we are talking about 1100 years each. And also Fraumünster, which was dissolved during the Reformation, had at that point existed for almost 700 years. Over long time frames, much could and did happen – wars destroyed fields and farms. Crop failures due to storms and hail caused famines. Bailiffs and mayors gradually „took over“ the properties they were only meant to hold in trust and claimed them as their own. Epidemics, such as the plague in the 14th century, left fields fallow because there were no longer enough farmers to work them. The list of challenges is long and these are just some of the most important and typical examples.

However, faced with such challenges, monasteries developed long-term strategies in order to secure their possessions from embezzlement and wars as well as they could. Naturally, some institutions were more successful than others. One strategy was to bundle the patrimony in clusters nearby the abbey. This was done by selling (or exchanging) farms and lands that were located far away and buying farms that were located closer. Thus, for example, Notre-Dame’s possessions on the Rhine disappeared almost entirely from the documents by the late 12th century, while at the same time the landholdings in those seigneuries located closer to the abbey grew. Both Notre-Dame and Buchau were particularly successful in this, and they succeeded to cluster and increase their respective possessions between the 13th to the 15th century (see topography of power for maps illustrating this).

The situation was different in the case of Fraumünster. Here, the abbess repeatedly sold parts of the abbey’s patrimony, because the community had incurred financial debts. Selling off patrimony to meet one’s financial obligations gradually weakened the abbey, whose possessions shrank over time.

The long-term economic success of a monastery – even if it was initially as richly endowed as Fraumünster – thus depended on various factors. A very central factor was the managerial skills, policies and foresight of the abbesses and their officers.

AM

Further reading:

AdA H 1506, fol. 33 r.v.

C. A. Berman, “Later Monastic Economies”, in: The Cambridge History of Medieval Monasticism in the Latin West, Vol. II, 2020, S. 831-847.

H. Röckelein, “Monastic Landscapes”, in: The Cambridge History of Medieval Monasticism in the Latin West, Vol. II, 2020, 816-830.

Monasteries between Poverty and Wealth

Not all monasteries were as wealthy as Fraumünster in Zurich or Notre-Dame de Soissons. Especially in the late Middle Ages, urban convents often struggled to make ends meet. The rise of the mendicant orders in the late Middle Ages saw the establishment of many new communities, particularly in the fast-growing cities. Contrary to traditional monasteries, where entry was contingent on noble lineage and the payment of a high dowry, the new communities welcomed women from the urban middle class. These communities had to actively earn their sustenance. While male communities could do this through pastoral care and begging in the streets of the city, female communities did not have this opportunity. Typical forms of economic activity of urban convents comprised handcrafts, such as silk embroidery, book illumination and copying, along with teaching lay girls. However, depending on the monastic density, competition could be high. And not all communities succeeded in generating sufficient income. Some communities depended on support from the city or descended into poverty.

Monastic Criticism in the Late Middle Ages

During the 15th and 16th centuries, monastic life in general was increasingly criticized. In response, the 15th century in particular saw a multitude of monastic reforms. However, the number of theologians, who increasingly questioned the very nature of monastic way, grew larger. And during the Reformation, thousands of monasteries were dissolved – including Fraumünster and Klingental.

In late 1524, Fraumünster’s last abbess, Katharina von Zimmern, handed over all of the convent’s rights and possessions to the mayor and council of Zurich. While the process went relatively smoothly in Zurich, Basel’s Klingental nuns put up more of a fight, and they resisted their dissolution for many years. Only in 1557, almost 30 years after the city of Basel had embraced Calvinism and banned catholic practices, the last living nun of Klingental, Ursula von Fulach, gave up her resistance and left both the convent and Basel.

Beguines

Especially in the cities along the Rhine River and in Paris, there was another popular war of religious life: Beguines (women) and Beghards (men). Beguines and Beghards were women and men who wanted to lead an ascetic and devout life, similar to life in a monastery, but without committing to perpetually entering a monastic community. This way of life was especially popular among women.

In most cases, Beguines formed small communities in so-called Beguinages, where the women lived together. Depending on the size of the respective community, the women shared a single house, or they occupied whole quarters. The largest beguine communities were in Paris and Ghent, where several hundred women lived together and formed an independent city of women within the actual city.

While the respective way of life of individual Beguine communities could differ, all Beguines led a pious, chaste, and communal life. Since they never established a formal order, they were legally not subject to the Church but to the particular town in which the community lived. As a result, resistance within the Church grew from the late 14th century, and popes and bishops tried time and again to ban Beguine communities or to incorporate them into local religious orders. While there was never a comprehensive ban, the popularity and influence of Beguinages began to dwindle and they no longer played a major role after the 15th century.

AM / AS

Further reading:

Müller, A. Totgesagte leben länger. Das Kloster Klingental als Verwaltungseinheit in der Alten Eidgenossenschaft, in: Hirbodian/ Scheible/ Schormann (Hg.) Konfrontation, Kontinuität und Wandel […], Ostfildern 2022.

Wegner, S., Beginen, Klausnerinnen und andere Fromme Frauen im Raum Koblenz: geistliche und weltliche Netzwerke im späten Mittelalter, Mainz 2017.

Reichstein, F.-M., Das Beginenwesen in Deutschland, Berlin 2017.

Strocchia, S. T., Abbess Piera de’ Medici and her kin: gender, gifts, and patronage in Renaissance Florence, Renaissance Studies, 2013.

Power of the Abbesses

An abbess governed the abbey internally and represented it externally. She was the head of her monastic community. The respective authority of an abbess over her community could vary between individual convents and monastic orders. Some communities, such as the Dominican nuns of Klingental, had no abbess at all – the head of their community was a prioress. Other community’s had abbesses whose authority was comparable to that of a bishop. Thus, the abbess of Las Huelgas appointed priests and called synods, while the abbess of Fontevraud led an independent monastic order comprised of both men and women.

The Head of a Monastic Community

In general, the abbess was to be a model for the rest of the convent community – she was to lead them spiritually, but also provide for them and protect them from hard times. In her tasks, the abbess was supported by the cellarer, the convent’s chief economist who was also responsible to ensure adequate food supplies. Usually, the abbess wielded disciplinary authority over the convent’s nuns. She thus had the right to punish their misconduct. If disciplinary measures needed to be imposed, this usually happened in the daily chapter meeting with the entire convent present. However, abbatial authority was bound to convent laws. When punishing a nun for an offense, the monastic rule or the convent’s statutes determined the severity of punishment. In those communities that were comprised of both women and men, as was the case in Fontevraud and Buchau, the abbess was also in charge of the male members who had to obey her. In addition to the convent members in the narrow sense, also a number of lay persons and serfs belonged to the monastic family, and as such, they were subject to the abbess and her jurisdiction (see below).

Secular Dominion

In addition to their monastic charges, many medieval abbesses also exercised various secular authorities. In principle, an abbess could exercise all types of rule common in the Middle Ages. These included seigneurial authority, including jurisdiction, over sometimes vast estates where the abbess acted as ruler over the people living and working the land. Particularly in the case of large and remote seigneuries, an abbess often appointed secular administrators (mayor or bailiffs; see: The Monastic Economy). A monastery’s seigneuries provided the community with various taxes and revenues. These could be rendered in form of grain, wine, livestock or money. Often a monastery even owned serfs. Serfs were unfree peasants, who were obliged to perform certain labor services and were required to pay specific taxes. They even needed the abbess’ permission in order to marry.

Financial Managers

As head of their monastic community, abbesses had to ensure the economic soundness of their institution. They oversaw the administration of the monastic patrimony;they made sure that all the money owed to the monastery came in and that everyone in service of the community received their payment. Thus, among other things, abbesses were also the CEOs of their community.

While not all monasteries were rich, some convents rose to become considerable local economic forces. One example ofsuch a local economic force was àKlingental of Basel. Klingental attained this position through clever investments in real estate and through buying rents. Buying rents was a means for Christian institutions to circumvent the canonical ban of money lending for interest, although it served the same purpose. A person “sold” an annual rent to a monastery for a given sum of money. For instance, in exchange for receiving the sum of 10 Gulden, John agrees to pay Klingental 60 Kreuzer annually. 60 Kreuzer are the equivalent of 1 Gulden. In other words, after ten years of payment, Klingental broke even, and in year eleven, the convent was making a profit. The medieval system of rent buying was similar to taking out a loan from a modern bank – and at a very high interest rate at that. However, legally, the rent economy did not qualify as money lending (which was illegal for Christians), and medieval monasteries all over Europe came to widely use this form of investment.

Judges

In the Middle Ages, there were three degrees of judicial power: low, medium and high justice. Low Justice mainly dealt with minor offences -including property disputes or inheritance matters. As seigneurs, many abbesses habitually wielded this form of jurisdiction. High Justice meant the right to hold blood court. These courts dealt with offenses punishable by torture or even death sentences. As a rule, monasteries did not exercise high justice. However, there were exceptions to this rule: in 1499 Buchau’s abbess was granted high and low justice over the villages of Kappel, Kanzach and Dürnau. Notre-Dame de Soissons is also a special case in this regard, as the abbess exercised all three degrees of justice over most of the abbey’s seigneuries. However, we may assume that abbesses generally did not hold blood courts themselves, but appointed mayors or bailiffs to do so in her place. As of 1215 (Lateran IV), all ecclesiastics were forbidden to be involved in any form of blood shedding (from this time onwards, clerics couldn’t be surgeons anymore, let alone judges at blood courts).

Example: Margarete of Werdenberg

A particularly large number of sources have survived from the judicial activities of the Buchau abbess Margarete of Werdenberg (1449-1496). The documents mainly deal with economic disputes, which were decided by the abbess’s court. The abbess herself did not always sit on the bench, but she sometimes appointed representatives to judge on her behalf. During the abbacy of Margarete of Werdenberg, she also decided that Buchau’s abbesses could pardon and free convicts in their domain. She was thus, so to speak, supreme judge and governor in one.

Margarete of Werdenberg served as Buchau’s abbess from 1449 until 1496, and she was a particularly active judge. The legal documents that have come down to us from her abbacy mainly deal with economic disputes. While Margarete also had mayors and bailiffs who could sit court on her behalf, she very often presided herself.

A Case for the Abbatial Court.

Buchau, 10 March 1474

In 1474, Margarete of Werdenberg had been abbess of Buchau for 25 years. During this time, she had presided over a great many cases like the following.

The abbess of the nearby convent of Heggbach, Elisabeth Kröhl, demanded that Margret Wagner, a peasant in bondage to the monastery, render the convent a hen annually. As a serf, Margret Wagner lived in a certain area, namely the bailiwick of Mietingen, and all serfs in this area paid this annual tax to Heggbach. However, Margret Wagner refused to pay the annual chicken. She claimed (or rather her husband, who represented her in court) that she was not a serf but lived in Mietingen as a free peasant, and did not have to render the annual chicken to Heggbach.

Since the bailiwick of Mietingen was one of Buchau’s fiefs, it was the abbatial court that was in charge of solving the conflict. After a thorough interrogation of the two parties, Buchau’s abbess passed the following judgement that was typical for judgements in such cases: Whether or not she was a serf, Margret Wegner had to render the annual hen as long she lived in the bailiwick of Mietingen. However, she only had to pay the hens from then on – any outstanding payments were waived.

AS

Further reading:

Schmitt [Hirbodian], S., Die Herrschaft der geistlichen Fürstin. Handlungsmöglichkeiten von Äbtissinnen im Spätmittelalter, in: Fürstin und Fürst…, Stuttgart 2014, S. 187-202.

Regesten 819 – 1500, bearb. von Seigel, R./Stemmler, E./Theil, B., Stuttgart 2009.

Relationships beyond the Monastery Walls

Although for many female monastic communities, enclosed life was at least nominally required, nuns often maintained multi-layered relationships beyond the cloister walls. Thus, they not only communicated through letters with other convents, but also with their respective families. However, convents often also needed to maintain direct relations with the world around them – they needed to interact with their mayors, bailiffs, and other administrative staff. They needed to communicate with the priests who ministered to the community; and if the abbess had judicial rights, she quite naturally would have a lot of contact with a great many people. Thus the requirement of living an enclosed life without ties to the external world was very difficult.

The Family

Sometimes we can trace communication between convent members and their family, as this often happened through letters. Communication by letter played a major role in the Middle Ages, and especially for cloistered nuns, it was an alternative to personal conversation. However, direct communication was generally possible even in strictly cloistered monasteries. In such places, meetings between a convent member and somebody from outside the convent usually happened at a so-called àspeech window. The window was often covered by cloth and sometimes metal, so that neither the nun could see her interlocutor, nor could her interlocutor see her. Moreover, there were no private conversations allowed. If a nun talked to somebody through the speech window, there would be at least one more convent member present to listen in on the conversation and make sure that no indecent things were said.

However, such precautions were not always followed to the letter. And some families succeeded in establishing great influence over the convent in which their daughters were nuns and abbesses. Aristocratic families in particular, sought to secure the monastic offices for their daughters – naturally, the abbatiate in particular was sought after. And sometimes, families succeeded to establish veritable monastic dynasties (click here to learn more about Family Politics).

The speaking window of the Poor Clares monastery in Pfullingen from the 14th century. The nails ensured that no one gets too close to the window. This photo shows the secular side. © Wikimedia Commons.

While epistolary communication was a principle means to communicate with the outside world, especially for cloistered communities, un-cloistered monastics, such as in Buchau or Klingental, were able to meet family members in person outside of the convent. Naturally, there were also regulations here. However, especially in aristocratic convents, these may not always have been followed very strictly.

AM / AS

Further reading:

Müller, A., From the Cloister to the State. Fontevraud and the Making of Bourbon France (1642-1100), London 2021, S. 72-74.

Signori, G., Wanderer zwischen den ‚Welten‘ — Besucher, Briefe, Vermächtnisse und Geschenke als Kommunikationsmedien im Austausch zwischen Kloster und Welt, in: Krone und Schleier. … München 2005, S. 131-141.

Kleinjung, C., Geistliche Töchter — abgeschoben oder unterstützt? Überlegungen zum Verhältnis hochadeliger Nonnen zu ihren Familien im 13. und 14. Jahrhundert, in: Familienbeziehungen… Stuttgart 2004, S. 21-44.

Family Politics

Especially in aristocratic families, it was common to send one or even several daughters to a convent at a young age. There, the girls were educated and got acquainted with monastic life early on. However, in those cases, family ties usually remained strong despite the early separation. And that was indeed intended, as placing daughters in influential convents was usually part of an aristocratic family’s religious and political strategy.

Memoria

There were several reasons for a family to send their daughters to a convent. On the religious side, oblation, Latin for „sacrifice“, was a central motive. The oblation of one or several daughters was usually religiously motivated. In the convent, the young nun would pray not only for her relatives living in the world, but also for those who had already died, thus ensuring their salvation. In the Middle Ages, prayer in general was believed to be a tool to save souls from the Purgatory, and prayers of nuns were considered to be particularly effective. One important aspect of oblation was therefore to secure salvation through memoria.

Politics

In addition to religious motives, political and strategic ones also played an important role. It is important to bear in mind that religious and political motives did not mutually exclude each other in the minds of medieval people but went hand in hand.

Aristocratic families were generally interested in sending their daughters to one (or several) monasteries that were particularly rich in land and power. By sending daughters to a convent such as Notre-Dame, Buchau or Fraumünster, their families could try to influence the administration of the respective institution – especially if their daughter rose to one of the influential offices, such as that of the cellarer or even abbess.

It is therefore not surprising that certain family names appear in clusters in particularly rich monasteries. Sometimes, we can find even veritable convent dynasties, where cousins, aunts, and nieces lived together and traditionally held certain offices. Often their male relatives also held important offices – thus, it is not uncommon to find that the abbess’ uncle was the local bishop, and her brother the convent’s bailiff responsible for the protection of the monastery. Particularly during the early Middle Ages, the boundaries between convent and the world, and between monastic and private property, were fluid. Thus, it was customary that Fraumünster Abbey paid parts of the dowry for the daughter of the German King.

However, since the High Middle Ages, reforms repeatedly sought to cut the often symbiotic ties between a monastery and its aristocratic patrons. Although monasteries stopped providing dowries for royal daughters after the 11th century, connections between aristocratic families and feudal monasteries tended to remain close. And the nobility continued to place daughters in influential monasteries close to their own territories also in the late Middle Ages. To attain their ends, some families even used violence to secure an influential abbacy for their daughter. Thus, armed men of the Couhé family occupied the Abbey of Ste. Croix in Poitiers in the 15th century to impose their candidate rather than having the candidate of the rivalling Amboise family succeed. And also, the Count of Bourbon-Vendôme sent armed men to Fontevraud in 1506 to help his sister,à Renée, impose her authority over rebelling monks.

The Aristocratic Families of Fraumünster

The first abbesses of Fraumünster were all of royal blood. As Louis the German (c. 806-876) had endowed the monastery with numerous items of his personal possessions, he wanted to make sure that their administration would be in loyal hands. And loyal hands meant family hands. Thus, the abbey’s first three abbesses were Louis’ daughters (Hildegard c. 853–856/59 and Bertha c. 857–877) and his daughter-in-law (Richardis 878–893). In later centuries, Fraumünster’s nuns and abbesses were not of royal blood anymore, but were recruited from the high aristocracy of Zurich, Thurgau, and Burgundy.

The Noble Families in Fontevraud and Notre-Dame

Also among the abbesses of Fontevraud and Notre-Dame, certain names appear in clusters. The Dukes of neighboring Brittany provided a total of four abbesses, including the order’s first reforming abbess, Marie de Bretagne. And between 1491 and 1670, abbesses from the House of Bourbon continuously governed Fontevraud. At the time, Fontevraud became the Bourbons’ monastic headquarters. Their daughters were educated here and then dispatched as abbesses to important, i.e. rich, French monasteries. After all, only one in each generation could govern Fontevraud itself.

The picture is similar in Notre-Dame of Soissons. Here too, certain family names appear in clusters. Between 1189 and 1273, three abbesses from the House of Cherisy ruled Notre-Dame. Other influential families whose names appear time and again are the Bazoches, Châtillon, Descronnes – and, from the 16th century onwards – Bourbon.

AM / AS

Further reading:

Theil, B., Das Bistum Konstanz. 4: Das (freiweltliche) Damenstift Buchau am Federsee, Berlin/New York 1994.

Wyss, G. von, Geschichte der Abtei Zürich. Beilagen; Urkunden nebst Siegeltafeln, Zürich 1851/58.

Edwards, J., Superior Women. Medieval Female Authority in Poitiers’ Abbey of Sainte-Ctroix, 2019, S. 236-242.

Müller, A., From the Cloister to the State, 2021, S. 159-162.

Signori, G., Memoria im Frauenkloster, in: Nonnen. Starke Frauen im Mittelalter, 2020, S. 31-36.

Legal Conflicts with the World

Because of the many different possessions a monastery owned, and the various rights abbesses wielded over them, legal conflicts were common. These conflicts usually arose from rivalling claims to power, from uncertainties about who owed what kind of revenue, or from crimes such as theft. Medieval society was a litigious one and thus engaging with legal disputes of some sort were almost part of the daily routines of an abbess. And the abbess (as representative of her convent) could be on either side – she might be one of the litigating parties or the judge mediating the conflicts of others.

Economic Disputes

As discussed here, many convents and their abbesses were feudal lords, and as such they had extensive rights over land and people. As feudal lords, they collected a number of dues in forms of natural goods (naturalia) and money. Conflicts over such revenues were particularly frequent, and they often arose when another party, such as a former mayor, bailiff or a town, laid claim to properties in the possession of a monastery. Other typical sources of conflict were questions of payment for people in the service of a monastery.

Example: Judenta of Hagenbuch

In 1249, Judenta of Hagenbuch had served as abbess of Fraumünster for twenty years. On June 24th of that year, the abbess received a letter from Constance asking her to appear at the episcopal court. There, a case brought against the abbess of Fraumünster, by the parish priests of Altdorf and Bürglen, was to be decided. The dispute centered on the fourth part of the tithe quarter. The tithe quarter was meant to cover living expenses of the priests and those for the upkeep and furnishing of the church buildings. The fourth part of this tithe quarter, i.e. 25% of it, was usually paid to the episcopal curia – it was a sort of tax.

The dispute centered on the question of who had to pay for the episcopal tax. The parish priests demanded that the abbess and nuns pay both the priests’ wages and the tax to the episcopal curia. That is, they demanded the tithe quarter for themselves and wanted the abbess to pay the tax in addition rather than it being taking out of their “paycheck”. Naturally, Abbess Judenta of Hagenbuch contested the demand and insisted that the priests had to pay the tax themselves.

When the arbitrators had heard all witnesses and agreed on a verdict, they invited the litigating parties to come to Constance to hear their decision. Upon receipt of the letter, Judenta of Hagenbuch undertook the two-day journey east and travelled across Lake Constance to Constance. There, she heard a verdict that certainly pleased her – the episcopal court ruled that the priests and not the abbess had to pay the tax.

Dispute with the City

Urban monasteries, such as Fraumünster in Zurich or Klingental in Basel, frequently found themselves in conflict with city council or other representatives of the citizenry.

In Zurich, conflicts between Fraumünster and the city became frequent in the late Middle Ages. Thus, on 1470, Abbess Anna of Hewen (1429-1484) and her convent litigated with the mayor and council of Zurich about the latter’s interference in convent matters. Eventually, the Bishop of Constance mediated the conflict – in favor of the city. The nuns had to accept the financial administrators (Amann and Pfleger) whom the city had appointed to oversee the abbey’s notoriously poor bookkeeping. With this legal success, the city of Zurich gained far-reaching control over Fraumünster’s finances. This type of dispute was not only about bookkeeping, but also about asserting power. It was in the interest of the city to affirm its own position and weaken that of the convent, which had used to be the actual city ruler (read more about the history of Fraumünster here).

Reforms

Monastic reforms were another frequent source of conflicts. A case in point for such a conflict is the (failed) reform of Klingental. In 1480, the city of Basel and the town’s reform clergy sought to introduce observant life in Klingental. However, Klingental’s nuns very much opposed this desire – and put up an impressive resistance. When members of the city’s reform clergy entered the convent to inform the nuns of their obligation to change their lifestyle, the nuns made so much noise that the envoy could not make themselves heard – and what is not heard cannot be followed. However, the city was not about to give up easily. The council had the most rebellious nuns arrested, and had thirteen reform sisters, i.e. nuns who were already observant, move into the convent. However, through litigation and with the help of their families and their far-reaching political networks, the rebellious ultimately prevailed. In 1483, Klingental’s nuns threw out the reform sisters. Apparently, this happened so violently that the convent church needed to be newly consecrated afterwards! Until the convent’s dissolution during the Reformation, Klingental’s nuns continued their accustomed lifestyle, unreformed.

While we usually do not have as much detailed information about a monastic rebellion against external interference, these types of conflicts surrounding reforms were typical in late medieval convents.

AS

Further reading:

Vischer, L./Schenker, L./Dellsperger, R. (Hg), Ökumenische Kirchengeschichte der Schweiz, Freiburg 1994.

Wyss, G. von, Geschichte der Abtei Zürich. Beilagen; Urkunden nebst Siegeltafeln, Zürich 1851/58.