The Beginnings

Desert Fathers and Mothers

The so-called desert fathers and mothers appeared in the late 3rd century. Devout early Christians, men and women, took to the deserts of modern-day Egypt and Syria to escape the persecutions of Roman Emperor Diocletian (284-305). However, when persecutions of Christians ceased in the 4th century, men and women continued to voluntarily choose life in the desert. There, they sought seclusion from worldly concerns and to live an ascetic life dedicated God. The harsh life in the desert – unbearable heat during the day, bitter cold at night, little food and water – allowed these first monks and nuns to live a perpetual martyrdom. In their belief, this brought them particularly close to God.

The First Monastic Communities

The most famous desert hermit was Anthony of Egypt (c. 251-356). Anthony came from a well to do family in Lower Egypt. Shortly after inheriting his parents’ lands, he gave away all his possessions, and he retreated to the desert around 275. Anthony soon became famous for his rigorous asceticism and closeness to God, and like-minded people began to settle in the vicinity of his cave. And, Anthony became the leader of a group of hermits seeking God.

Other groups of desert hermits also appear in the early 4th century. Pachomius (292/298-346) was the founder of a monastic association near Thebes in Egypt. His was the first community of monks who wanted to live a life consecrated to God in a community rather than as individual hermits. Pachomius‘ sister, Mary, founded a women’s monastery that followed the same ideals. The communities of Pachomius and Mary proved to be role models for other communities which soon were founded all over north Africa and Anatolia. While there were certain differences between individual institutions, they all embraced a life of poverty and abstinence, dedicated to prayer and service.

The First European Monasteries

Marmoutier near Tours in France was among the first monasteries founded in Europe. According to legend, Martin of Tours (c. 316– † 397) lived as a hermit before the people of Tours urged him to become their bishop. As a hermit, Martin quickly acquired a reputation as a holy man, and soon a group of disciples joined him. Together they formed one of the earliest monastic communities founded in Europe. However, the most influential early monastic foundation would be that of Benedict of Nursia (c. 480- c. 560†). Around the year 529, he founded a monastery on Montecassino (Italy) and he wrote a rule that was to regulate communal life. The so-called Benedictine Rule would come to shape medieval monasticism and continues to shape modern monasticism.

AM/AS

Further literature:

Melville, G., The World of Medieval Monasticism. Its History and Forms of Life, Collegeville 2016.

The Monastic Space

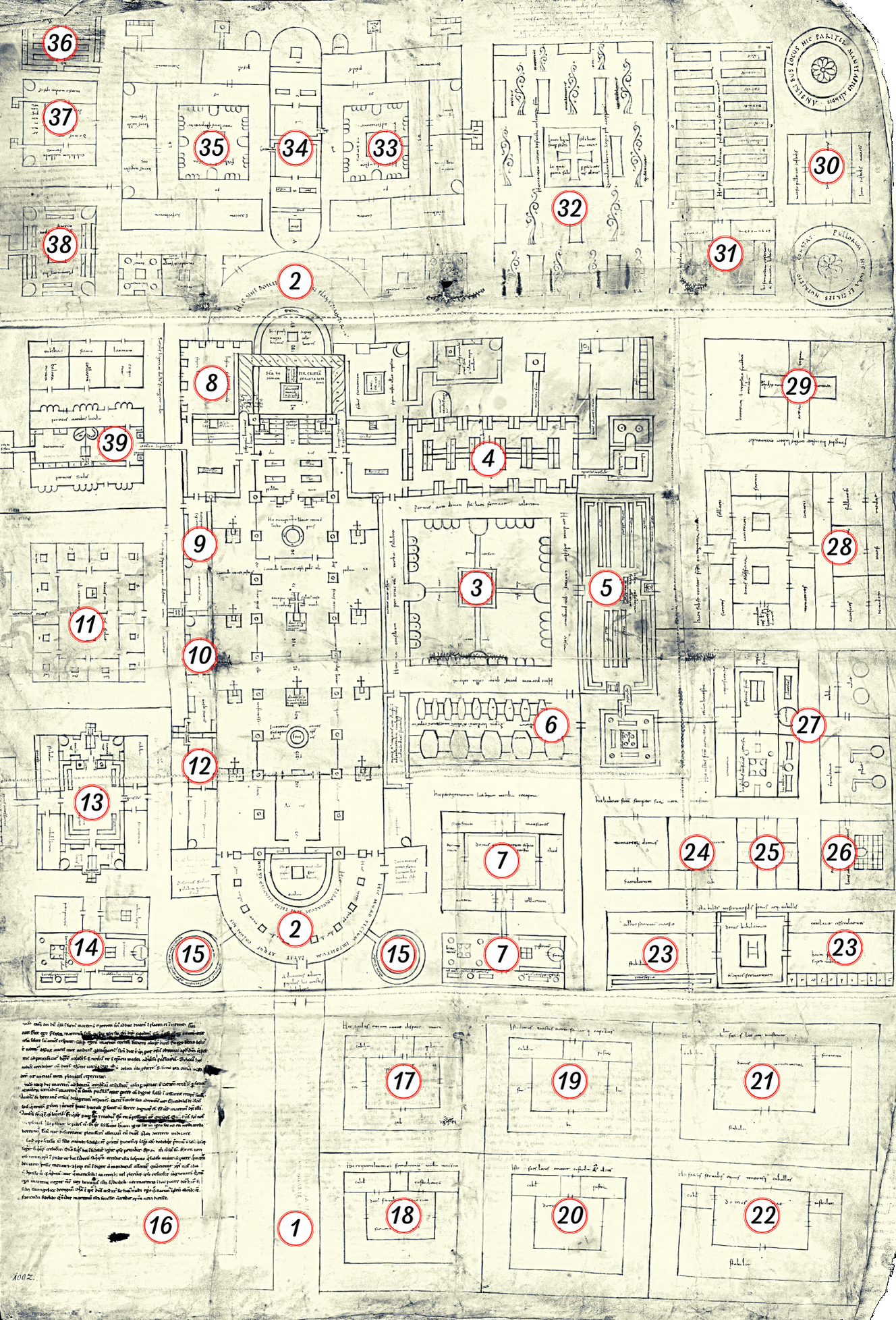

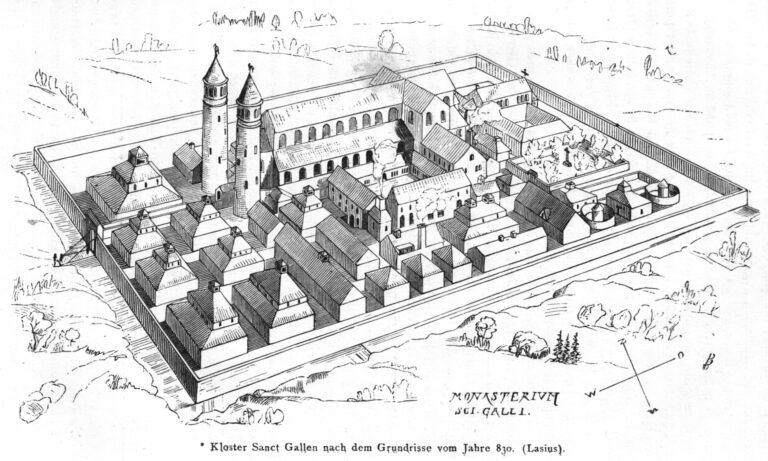

The monastic space of each community differed, as it was naturally adapted to both the size of the community and their surroundings. However, the main elements that characterized the medieval cloister in Europe were identical. The so-called Plan of St. Gall, dating from the 9th century, depicts an ideal monastic compound.

The Plan of St. Gall divides the monastic compound into a number of distinct sections. At the center is the church with the cloister. Adjacent to them are the abbot’s quarters and the monks’ communal dining hall. The dining hall is connected to the kitchen, which in turn is adjacent to the brewery and bakery. On the compound, but separated from the community’s living spaces, is an area for the sick and their doctors and yet another for novices. All of them are allocated their own church and cloister. Additionally, a large area of the compound is set aside for livestock and storage. There are stables for goats, pigs, sheep and cows, along with a number of storage rooms for grain, a mill and even an oil press as well as houses for the lay servants.

Overall, the monastic compound as depicted in the Plan of St. Gall is setup to allow the community to live self-sufficiently. It is noteworthy that about half of the buildings do not serve a religious purpose but served to secure the sustenance of the community. In this concrete case, a compound of the size as depicted on the plan would have been able to cater to the needs of a community of up to 350 people. While most monastic communities were much smaller than that, the ratio of religious and economic buildings was typical for a medieval monastic complex.

The Individual Buildings

- Entrance to the church from outside the walls

- The church with several altars

- Cloister

- Heating room; above: Dormitory (sleeping room)

- Refectory (dining room)

- Cellar (stores)

- House for pilgrims and poor travellers, with adjoining brewery and bakery

- Scriptorium (writing room); above: Library

- Guest house for monks

- Schoolmaster’s quarters

- School

- Porter

- Accommodation for high-ranking guests

- Brewery and bakery for high-ranking guests

- Towers

- Large building with uncertain use

- Sheepfold

- Servants‘ quarters

- Goat shed with herd’s quarters

- Pigsty with herd’s quarters

- Cattle shed with cowherd’s quarters

- Horse stable with quarters

- Stable for oxen, mares and foals with hay storage and sleeping quarters for servants

- Workshops for coopers and turners

- Storehouse for brewer’s grain

- House for drying fruit

- Brewery and bakery for the resident monks with adjacent kitchen on the left and access to the dining hall

- Workshops for shoemakers, saddlers, sword and shield makers, blacksmiths, etc.

- Granary and threshing floor

- House of the poultry keeper with adjoining stable for chickens and geese

- Gardener’s house with adjoining vegetable garden

- Cemetery and orchard

- Cloister for novices and their instructors

- Church for the novices and the sick

- Cloister and accommodations for the seriously ill

- Medical herb garden

- Doctors‘ room, pharmacy and patients‘ rooms

- Building for medical use

- House of the abbot, with passage to the church and main monastery

While the compound depicted on the Plan of St. Gall never existed in the Middle Ages (the plan depicts an ideal monastery), the compound is being built today. For some years, a team of archaeologists, historians and enthusiasts have been building the monastic compound as depicted on the famous map. They use only resources and tools that would have been available to medieval builders. You can find out more about this project on the Campus Galli page.

Women's Convents

While the Plan of St. Gall depicts a male compound, female monastic complexes did not differ much from them. There are a number of representations of female cloisters that provide insights. For example, a seventeenth-century map of Basel shows the Klingental Convent. One can clearly see the central position of the church on the compound. Adjacent to the church is a cloister and a large convent building for the nuns, with other smaller buildings on the opposite side. There are also cemeteries in the area of the monastery. The nuns were laid to rest in Klingental’s courtyard and a separate cemetery was reserved for the convent’s lay donors.

The monastic cemetery was not only a place of eternal rest, but also of representation. In the late 13th century, the abbess of Fraumünster, Elisabeth of Wetzikon (1269-1298), had the abbey’s cemetery redesigned. This happened at the same time as the comprehensive constructions of the Münsterplatz, the square in front of the abbey church. During the reconstruction, the formerly enclosed cemetery was transformed into an open square, and also the Münsterplatz was extended. The aim of these reconstructions was to provide the abbess with a larger public stage, and to put on display the long line of important former residents of the abbey.

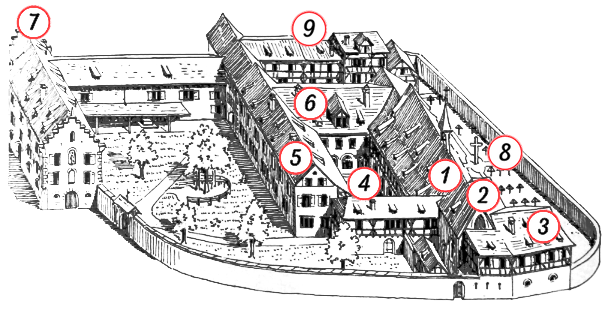

Buildings of the St. Catherine's Monastery

While the compound of the Dominican nunnery of St. Catherine was much smaller than the one depicted on the Plan of St. Gall, there are nevertheless some parallels – especially in regard to the ratio of living and economic buildings.

- Church (from 1368)

- Sexton’s house (from 1484)

- Flat of the reading master

- Cloister

- Convent building

- Old refectory (dining room)

- New refectory (dining room)

- Cemetery

- Economic buildings

AM / AS

Further reading:

Campus Galli, Klosterplan, url: https://www.campus-galli.de/klosterplan/ (letzter Zugriff am 5 Aug. 2021).

Shepherd, W. R., Historical Atlas, New York City 1911, url: https://legacy.lib.utexas.edu/maps/historical/shepherd/monastery_st.gall_swiss.jpg, (letzter Zugriff am 5 Aug. 2021).

Wild, D., Zürichs Münsterhof – ein städtischer Platz des 13. Jahrhunderts? Überlegungen zum Thema „Stadtgestalt und Öffentlichkeit“ im mittelalterlichen Zürich, in: Fund-Stücke – Spuren-Suche, S. 327-352.

Noviziate and Profession

Every young woman who wanted to become a nun had to undergo several years of training in the monastery. This training is called novitiate. During this period, the novice learned about the rules and customs of the convent, and received also a general education – reading, writing, math, Latin, theology, etc. The novitiate was also a period of testing. The novice mistress, who was responsible for their education, and the older nuns, had to decide whether the girls were suited for convent life. However, for the most part, girls who were accepted as novices, whose parents had paid the dowry, would then be accepted in the ranks of the nuns. The novitiate ended with the profession, i.e. the perpetual vow to live a life dedicated to God. After the profession, the new nun was a full member of the monastery enjoying all the rights of a cloister nun, including a seat and voice in the chapter.

The Perpetual Vow

There were a number of ceremonies that marked the transition from novice to nun. The dressing was an important ritual on this path, during which the novice received her monastic habit and veil. The full habit marked the new nun as a full member of the convent. The perpetual vows were the most important step in the transition. By taking the vows, the nun dedicated herself to a life of poverty, chastity, and obedience. The vows were perpetual – once taken, they could not be recanted. The Profession usually took place in a liturgical setting and somewhat resembled a wedding ceremony: by taking the vows, the novice became the bride of Christ

Canonesses

Unlike Benedictine nuns, canonesses did not take perpetual vows. Nevertheless, they also had specific rituals, during which the new canonesses promised to obey her abbess to follow the rules of the community. She also received a new garment – a choir robe – and henceforth shared the same rights as the other canonesses. As their vows were not perpetual, canonesses theoretically had the right to leave the cloister to get married if they chose to. However, very few canonesses seem to have actually left their communities.

AS

Further reading:

DeMaris, S.G. (Hg.), Johannes Meyer: Das Amptbuch, Rom 2015.

Klapp, S., Das Äbtissinnenamt in den unterelsässischen Frauenstiften vom 14. bis zum 16. Jahrhundert. Umkämpft, Verhandelt, Normiert, Berlin/Boston 2012.

Schlotheuber, E., Klostereintritt und Übergangsriten. Die Bedeutung der Jungfräulichkeit für das Selbstverständnis der Nonnen der alten Orden, in: Frauen – Kloster – Kunst…, Turnhout 2007, S. 43-58.

Monastic Rules and Habits

Living in a monastic community meant living according to strict rules – usually a version of the Benedictine of Augustinian Rule. At Notre Dame de Soissons and Fraumünster, the nuns lived according to the Benedictine rule. The Fontevrist rule was also based on the Benedictine Rule. The Cistercian nuns of Las Huelgas also lived according to an amalgam of Benedictine Rule and a constitution specifically for Cistercian monasteries, the Carta Caritatis. The Dominican nuns of Klingental lived according to the Rule of St. Augustine, and certain canonesses, such as those of Buchau, did not follow any actual rule but lived according to statutes specific to their institution.

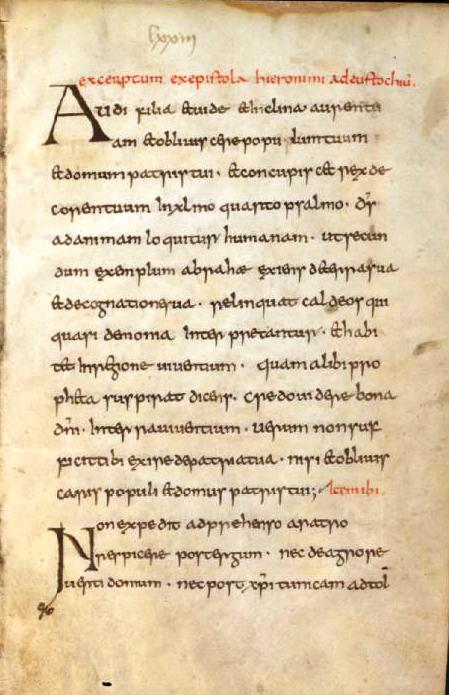

The Rule of St. Benedict

The Rule of St. Benedict, also called the Benedictine Rule, was written by Benedict of Nursia (c. 480- c. 560†), for his community of monks of Monte Cassino around 529. This rule was successful, and it was quickly adopted by other congregations as well, including by communities of nuns.

However, it would take another 300 years before the Rule of St. Benedict became the most followed rule in Christian Europe. The monastic reforms carried out by Benedict of Aniane (c. 750-821†) with the approval of Emperor Louis the Pious (778-840†) and made universal at the Synod of Aachen (816), made the Benedictine Rule the dominant monastic rule – which it is until this day.

The Rule consists of several chapters which address and regulate community life, the abbatial government, communal prayer, and daily routines along with dietary restrictions.

Structure of the Rule of St. Benedict

Prologue: Objective of the Rule

Chapters 1-3: Community and Abbot (Abbess)

Chapters 4-7: Doctrine of Virtue

Chapters 8-20: Doctrine of Prayer and Order of Divine Worship

Chapters 21-22: Internal Order of the monastery

Chapters 23-30: Sanction and Penalties

Chapters 31-57: Administration of the Monastery

Chapters 58-61: Rules of Admission of new members

Chapters 62-67: Offices and Duties

Chapters 68-73: Communal Life

The Augustine Rule

In addition to the à Benedictine Rule, the Rule of Augustine was the second monastic rule that was widely used in medieval Europe. Augustine of Hippo (354-430†), the most important church father and philosopher of Christian antiquity, wrote the rule when he was bishop of Hippo. As bishop of Hippo (located in present-day Algeria), Augustine was responsible for the monasteries there. Today, scholars believe that Augustine originally wrote the rule to settle a dispute within a women’s convent. Consequently, his intention was not to write a comprehensive collection of laws, but rather an orientation meant to facilitate communal life. Before this collection of laws, it is not surprising that the Rule of Augustine mainly consists of general guidelines: The daily life of the community was to be devoted to prayer. They should live celibate and keep silent during meals. No one should have personal possession and everything was to be shared communally. Finally, all members of the community owed obedience to their superior. The rule, which is much shorter than the Benedictine, mainly addresses those aspects that could cause problems in a community.

The Statutes of the Canonesses

The Synod of Aachen (816-819) decided about a number of church reforms, including monastic reforms. Henceforth, monastic communities withing the Frankish Kingdom should only follow either the Benedictine or the Augustinian rule. Excepted from the decision were a number of female communities – usually with close ties to the Frankish elite. For these canonesses, a set of rules was created: the Institutio sanctimonialium. As in a monastery where the Benedictine or Augustinian rules were followed, canonesses were also to have an abbess. They also had to pray the Liturgy of the Hours, attend mass and avoid contact with other sexes. However, unlike nuns, they were allowed to own private property and they did not take perpetual vows. àBuchau was home to a congregation of canonesses.

However, it is important to note that while nuns were theoretically required to live in poverty, in reality life at wealthy monasteries, such as Fraumünster or Fontevraud, differed little from that in congregation of canonesses.

AM / AS

Further reading:

Halinger OSB, K., Consuetudo. Begriff, Formen, Foschungsgeschichte, Inhalt, in: Untersuchungen zu Kloster und Stift, Göttingen 1980, S. 140-160.

Holzherrm G., Die Benediktsregel: Eine Anleitung zu christlichem Leben; Der vollständige Text der Regel, Fribourg 2007.

Melville, G., Die Welt der mittelalterlichen Klöster: Geschichte und Lebensformen, München 2012.

Parisse, M., Art. Kanonissen, in: Lexikon des Mittelalters, Tl. 5, München/Zürich 1991, Sp. 907f.

Schormann, A., Identitäten und Handlungsmöglichkeiten von Kanonissen im 15. und 16. Jahrhundert, Berlin 2020.

Daily Routines of a Nun

Life in a convent was marked by routines – every day was to be the same in every monastery. It was to be divided into alternating sequences of praying and working. In the Middle Ages, light determined the length of the hours. That is to say, rather than the day being divided into 24 hours of equal length, it was divided into twelve hours of light (from sunrise) followed by twelve hours of night (from sunset). During summer, the twelve hours of the day were thus longer than the twelve hours of the night; and vice versa in winter.

The morning began with communal prayer in the convent church. Afterwards, the nuns read the Bible, worked in the garden or kitchen or elsewhere, before the convent met again for prayer. During meals, one nun would read from the Bible, while the others listened and ate in silence. At least once a day, the nuns convened in the chapter, where they read the rule and addressed issues concerning their congregation. The rest of the day was marked by set prayer times. The firm daily routines were meant to leave little freedom for individual nuns.

Praying the Divine Office

Prayer was the red thread of the nuns’ daily life. The canonical hours structured the day dividing it into fixed times of prayer. The day started the early morning with Matins and Lauds and ended in the evening with Vespers and Compline. In between, there were the hourly prayers that took place at the first (prim), third (terce), sixth (sext) and ninth (non) hours of the light day.

If we “translate” this medieval prayer schedule and adapt it to our “clock”, we get the following. In summer, Matins could take place as early as 3 a.m. Lauds was prayed at sunrise at about 5/6 a.m. (and later in winter). Prim, the first hour of the day, followed around 6/7 a.m., Terce at about 9 a.m., Sext at noon and Non at about 3 p.m. After Terce, the nuns sat down to breakfast and then worked until Sext in the writing room, the convent garden or in the kitchen. After Sext, the nuns had their main meal of the day. Vespers took place around 6/7 p.m. Another light meal was taken afterwards, and the convent day concluded with Compline around 7/8 p.m. Afterwards, the nuns went to bed – to rise again before 3 a.m. to start the next day.

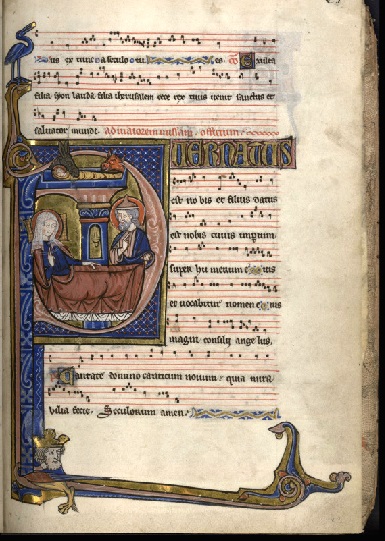

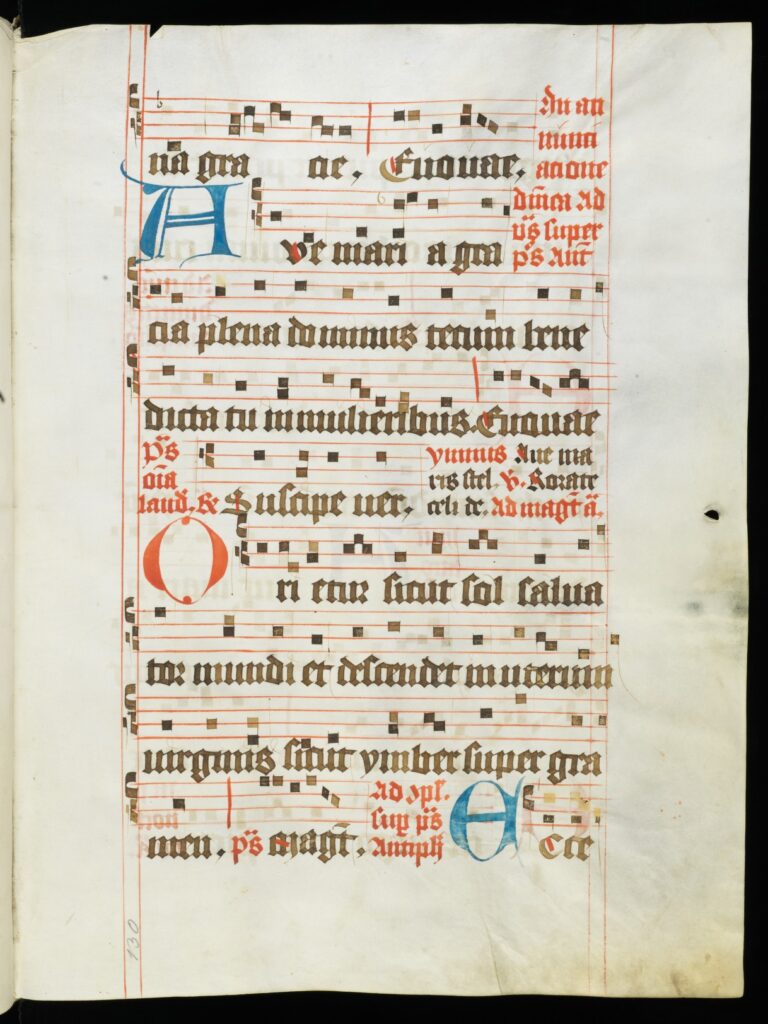

Gregorian Chant

Rather than silent prayer, the Divine Office was sung. Throughout the Middle Ages, the Gregorian chant was the song of the cloisters. It is a monophonic liturgical chant that originated in France in the 9th century and from there found its way into all western European monasteries. Essentially, Gregorian chants are sung psalms, songs and prayers from the Bible.

Here is an example of such chants – from the Graduel d’Aliénor de Bretagne, which was written in Fontevraud in the 14th century:

Daily Routine of an Abbess

Nuns were obliged to obey their abbess. In turn, the abbess had to guide her community, care for her nuns and be a role model to them in all things. Therefore, the abbess shared the daily routines of her community – she joined them in prayer times and for meals. However, the abbess was in charge of the economic and legal well-being of her community. She was therefore often allowed to leave the cloister to tend to her convent’s economic and legal business. The abbess was thus always both – a regular nun and manager of monastic affairs.

AM / AS / JR

Further reading:

Müller, A., Nonnen im Mittelalter – Ein geregeltes Leben fernab der Welt?, in: Nonnen. Starke Frauen im Mittelalter, Zürich 2020.

Schormann, A., Identitäten und Handlungsmöglichkeiten von Kanonissen im 15. und 16. Jahrhundert, Berlin 2020.

Monastic Education

Often girls entered the convent at a young age to become a nun. Prior to taking the veil, they received an extensive education at the convent school that would have been unavailable to them outside the cloister. For the successful running of monastery, it was crucial that its inhabitants were versed not only in reading, writing, and math, but also in theology and law.

Enclosure Management

Especially for those convents who had embraced strict enclosure, managing their patrimony could be difficult. If they wanted to take care of their own affairs, they needed to be knowledgeable in law (to solve conflicts), and they needed to know their arithmetic (for book keeping), and be good scribes (to converse with the outside world through letters). So, the higher the nuns’ level of education, the more independently they could conduct this correspondence behind the convent walls – with their administrators, servants, but also their relatives, and political and religious superiors. Moreover, because of their secluded life, external knowledge entered the cloister primarily in the form of book exchanges rather than through exchange with scholars. To be “up to date” in matters of religion, law, and science, nuns needed access to books (and they obviously needed to be able to read and understand them).

In the Scriptorium

The Scriptorium was the place where books were kept and, more importantly, copied. This could happen as a way of creating income. Monasteries would copy religious but also secular literature upon demand (we have to remember this is before the invention of the printing press – all books were copied by hand). However, also periods of monastic reforms were moments when book production in convents peaked, as the scribes produced the new liturgical handbooks. Naturally, it was important that the transcribing nuns knew both German and Latin in order to be able to read and copy the works before them.

While many convent libraries have been lost over time, researchers have been able to reconstruct the holdings of some of them. Thus, we know that the Dominican convent of St. Katharina of St. Gall had an impressive library. It contained at least 323 manuscripts in the 16th century. The convent’s 22 nuns’ scribes had compiled many of them by themselves. The inventory of the library, which has survived the erosions of time, shows that the nuns had at least a functional command of liturgical Latin. The high number of German-language Bibles, psalters, and plenaries also show that the nuns of St. Katharina possessed a great deal of religious and theological knowledge.

The Book-Legging of Regula Keller

Regula Keller was a nun at St. Katharina of St. Gall in the early 16th century. When the Reformation began to spread also in St. Gallen and monasteries were about to be dissolved in 1527, Regula feared for the safety of her convent’s library. She decided to smuggle manuscripts out of town. We know of this because of a letter discovered in one of Regula’s smuggled books. In the letter, Regula wrote:

„Dear Mother of our sister house in Appenzell, I, Sister Regula Keller of St. Katharina in St. Gall am sending you two books…. The reason for this is that there is such constant unrest here [in St. Gall] that we fear we will lose these things. I ask you not to tell anyone in our monastery that I sent them to you, because I did not ask permission to do so. Put this letter in one of the books so that if any of you perish, everyone will know where the books belonged. And pray to God for us, because if our convent should perish and all the sisters with it, at least you will have the books.“

Regula Keller was a nun who acted independently and ensured against all odds that her convent’s valuable books survived the upheavals of the Reformation. She is an example of the importance and love the nuns attributed to their books and to their education in general. While Regula was unable to prevent the dissolution of her convent and although she even had to serve a prison sentence for not giving up on her faith, she eventually succeeded to found the new convent of St. Katharina. The convent still exists today and is now located in Wil.

Convent Schools

Before the advent of universities in the later Middle Ages, monastic schools had been the unrivalled centers of education. However, while male monasteries then could (and often did) outsource the education to universities, for women, monastic schools remained the principal pillar of education throughout the Middle Ages. Both aristocrats and urban bourgeoisie desired to have their daughters educated in convent schools. For convents, in turn, the education of external girls was often financially interesting. However, the mixture of secular girls with novices destined for monastic life was subject to dispute. Reformers especially feared that the mingling with secular girls might corrupt the morals of young novices.

The School Lessons

Part of the school education was Latin instruction, which could mean two things: On the one hand, it could be limited to the future nuns learning the texts by heart, but on the other hand, it could also include a grammatical and lexical understanding of the Bible and an active mastery of the Latin language. In addition, the school lessons also included the training of a certain capacity for abstraction. The convent girls were supposed to learn how to interpret their experiences from a religious or mystical point of view.

Hildegard of Bingen: Hymns and songs (12th century).

A Visionary: Hildegard of Bingen

Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179) was certainly one of the most outstanding personalities of the Middle Ages. In the 81 years of her life, she led monasteries, recorded numerous visions, i.e. divine revelations, in writing, put her knowledge of medicine and nature to parchment, and she even composed music. Hildegard of Bingen’s public sermons, in which she relentlessly denounced the worldly transgressions of the clergy, were feared among Church leaders, and emperors and popes accepted her spiritual and religious authority.

Hildegard’s religious life began early. At the age of eight, she was placed in the care of the anchoress, Jutta of Sponheim. Jutta had built her hermitage in a Benedictine monastery, next to the monks’ choir. Together with another girl, Hildegard entered Jutta’s hermitage and the three were enclosed there in 1106. Jutta taught the girls Latin, and studied the Holy Scriptures and the teachings of the Church Fathers with them. Supposedly, Hildegard already experienced visions during this time. However, she only began to write them down in her 40s. Between 1141 and 1151, i.e. at the age of 42-53, she wrote Scivias („Know the Paths“). Hildegard submitted a first version of her visionary writings to Pope Eugene III. (1145-1153). She asked the pope and the participants of the Synod of Trier (1147/1148) to check if her visions came from God or the devil. The synod found Hildegard’s visions to be true and of divine origin. Hildegard was then ordered to keep writing down her visions.

In addition to writing down her visions, Hildegard was the author of books of medical and natural knowledge. Her Physica deals with natural history and her Causae et Curae with medicine. The Physica consists of 9 books with ca. 350 very detailed descriptions of plants, animals, precious stones and metals. In Causae et Curae Hildegard informs her readers about mushrooms and plants and their (supposed, but also actual) medicinal effects. In addition to visions and science, Hildegard was also active as a composer: She composed at least 77 hymns. Hildegard was thus a universally educated monastic woman.

AM / AS

Further reading:

Winston-Allen, A., The Observant Reform versus the Reformation: Women’s Scriptoria, Books and the Resistance, in: Konfrontation, Kontinuität und Wandel, Ostfildern 2022, S. 39-55.

Feldmann, C., Hildegard von Bingen. Nonne und Genie, Freiburg i. Br. 1995.

Mengis, S., Schreibende Frauen um 1500. Scriptorium und Bibliothek des Dominikanerinnenklosters St. Katharina St. Gallen, Berlin 2013.

Schlotheuber, E., Klostereintritt und Bildung. Die Lebenswelt der Nonnen im späten Mittelalter…, Tübingen 2004.

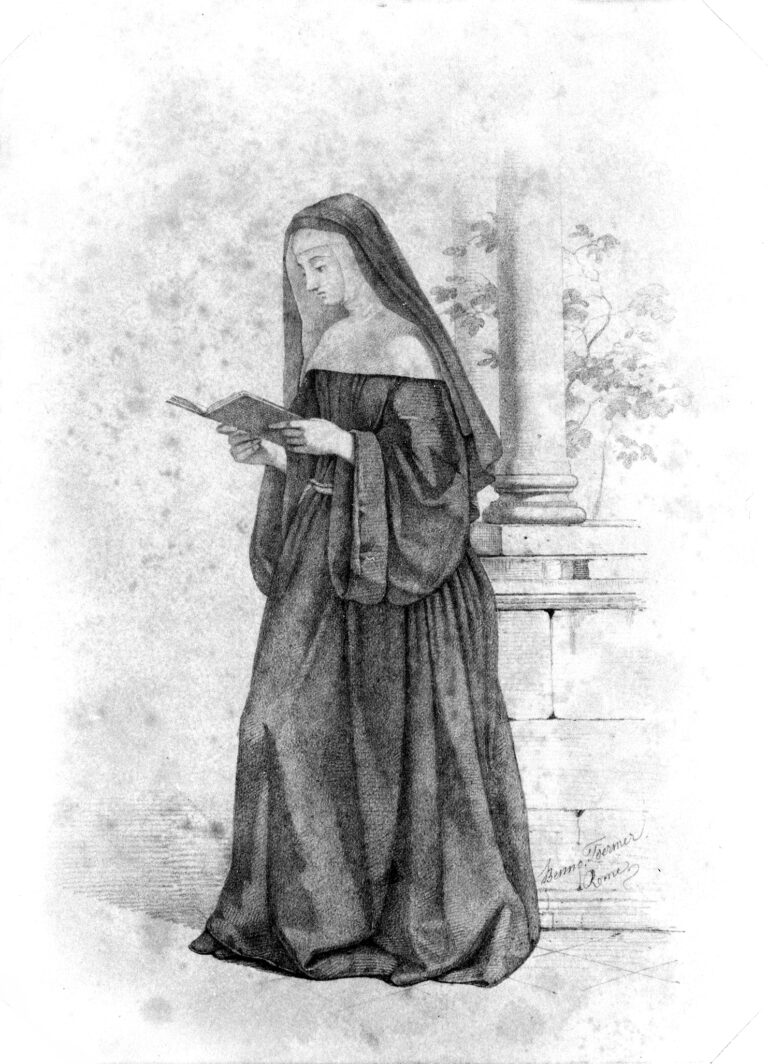

The Nuns' Clothing

The outfit of a nun consists of several elements. In addition to the habit, she wears a veil, an apron or shoulder robe (scapular), a belt (cingulum) and, on special occasions, an overgarment (cowl). The main garment is the habit, which is derived from the Latin word for posture and shape. It is woven from simple (and scratchy) wool and symbolizes a nuns’ life of poverty and chastity. Moreover, the habit’s specificities communicate to which convent or monastic order its wearer belongs. Thus, Benedictine nuns wear black and Cistercians wear white habits.

The Habit and Religious Communities

The specificities of a nun’s garments were revelatory for the monastic congregation she was a member of. Thus, Benedictine nuns (such as those of Notre-Dame de Soissons and Fraumünster) predominantly wore a black habit. Also, members of mendicant orders, such as the Poor Clares, wore mainly black clothing made of coarse wool, along with a black veil and sandals on their otherwise bare feet. Cistercian nuns, on the other hand, as in Las Huelgas, wore a combination of white and black. Dominican nuns, as in Klingental, wore a white undergarment and a black cloak. Clothing was also indicative of rank within the community. Thus, novices wore a white veil to distinguish themselves from the professed cloister nuns, who wore a black veil.

While the religious clothing of canonesses was similar to that of Benedictine nuns, they had more liberties, as they were allowed to possess both secular and spiritual clothing. When they went about their religious duties, canonesses also had to wear a habit with a veil. However, when they were not in church, they were often allowed to wear fashionable clothes that were often based on secular noblewomen.

AS

Further reading:

Constable, G., The Ceremonies and Symbolism of Entering Religious Life and Taking the Monastic Habit, from the Fourth to the Twelfth Century, in: Culture and Spirituality in Medieval Europe, Aldershot 1996, S. VII: 771-834.

Kuhns, E., The Habit. A History of the Clothing of Catholic Nuns, New York 2003.

Schlotheuber, E., Best Clothes and Everyday Attire of Late Medieval Nuns, in: Fashion and Clothing in Late Medieval Europe, Basel 2010, S. 139-154.

Schormann, A., Identitäten und Handlungsmöglichkeiten von Kanonissen im 15. und 16. Jahrhundert, Berlin 2020.

Food and Drink

In addition to prayer and work, eating and drinking were part of the daily routine in a convent. Meal times, food to be served, as well as the nuns’ behavior in the refectory were regulated. After Terce, at around 9.00 a.m., the nuns had breakfast, and after the Sext, they had lunch, which was also the main meal of the day. After evening prayer there was a light supper.

Monastic account books reveal to us what produce monasteries bought and thus tell us what they ate. Cereal products, such as bread, made up an important aspect of the meal. When available, the community also ate fresh fruit and vegetables. Meat was allowed, however not during Lent.

Eating and Drinking according to the Benedictine Rule

Chapters 39-41 of the Benedictine Rule engage with food. They allow for two cooked meals and one pound of bread (approx. 300 grams) per day, with fruit and vegetables to be served according to availability. According to the rule, between Easter (April) and Pentecost (June), the main meal was served at the sixth hour and another at the ninth hour of the day. Between September until the beginning of Lent (February), food was served at the ninth hour, and between Lent until Easter, food was only eaten in the evening, while fasting the rest of the day. It is important to note in Benedict’s rule that eating still took place in daylight. In addition to water, monastics were allowed a quarter of a liter of wine per a day. However, this was theory, and not all monasteries followed the rules closely.

Rules and Exceptions

The Benedictine Rule generally forbade eating meat. However, many medieval monasteries obtained papal privileges, so-called dispensations, which exempted them from this ban. Moreover, in the Middle Ages different definitions of meat prevailed thus, poultry, often did not count as meat. And beaver meat was considered fish and could therefore even be served during Lent. However, despite the discrepancies in definition and the cunning ways of circumventing extant rules, we should not expect excess of food and drink in medieval convents. Even wealthy convents that could pay for obtaining papal dispensations and afford the price of meat, abided by the dietary restrictions of Lent. During the fasting period, food was only allowed after Vespers, i.e. at around 7.00 pm.

AS

Further reading:

Holzherrm G., Die Benediktsregel: Eine Anleitung zu christlichem Leben; Der vollständige Text der Regel, Fribourg 2007.

Schormann, A., Identitäten und Handlungsmöglichkeiten von Kanonissen im 15. und 16. Jahrhundert, Berlin 2020.